Interior(ity) Design Fails

How NOT to Get In a Character's Head (Part 1 of 2 or possibly 3)

If you follow my Zillow posts (don’t worry, another is coming soon) then you know how much I love an interior design fail. What I love a lot less is a failure of interiority in fiction.

What could be worse than this zebra-and-lilac masterpiece? Fiction that doesn’t take us inside a character’s head, or does so super awkwardly, or accidentally breaks its own rules of point of view, or resorts to clichés when representing thought or memory.

If you’re writing fiction or memoir, here are eight mistakes you might be making (and how not to):

The Empty Head

(Very little interiority at all)

Here’s what it looks like:

Georgia filled Michael’s glass. “Here you go,” she said.

He scooped potatoes onto his plate. “They’re cold again,” he said, and he grabbed the remote off the table and turned on the news. There was an election going on in Canada.

Georgia said, “I know nothing about Canadian politics.”

Here’s what’s wrong with it:

Well, nothing, necessarily, in a section this short. But notice how we’re in no one’s head. Over many paragraphs and pages of this, we’re not going to feel like we know these characters at all. On rare occasion this works for a while—think of Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants,” which keeps this up for the three-page duration of the story—and if you want to try a truly objective point of view for longer, knock yourself out. But do it intentionally. Most of the time when I see this in student work, the student is not aware that for the whole piece, or for pages at a time, they’re not letting us in on anyone’s thoughts.

In my experience, there are six types of fiction writers who are particularly prone to this kind of neglect: current or former journalists, who’ve been taught not to speculate what people are thinking; lawyers (same thing—objection! speculation, your honor!); scientists (often trained in literal, technical writing); current/former screenwriters or playwrights, who are used to having to get everything across through action and dialogue; the poor souls who took “show, don’t tell” to mean you can only write action and dialogue; and people who watch a lot of movies but don’t really read, so what they’re writing is basically a screenplay.

Other writers are tempted, when writing a character who lacks self-awareness, or isn’t fully aware of their own motivations, to give them no thoughts at all. The thing is, no one’s head is just empty. That character could be thinking of other things, or she could be deluding herself, but she’s certainly thinking something.

Failure to Stop for Gas

(Not enough interiority in crucial scenes)

Here’s what it looks like:

Georgia saw a knife on the ground. She picked it up. She could feel her cheeks grow hot. She walked slowly to the bathroom door, listening to the end of Michael’s shower. The knife was heavy in her hand. He opened the door, and she struck, plunging the blade into [okay, that’s enough]

Here’s what’s wrong with it:

We’re clearly in Georgia’s point of view—she’s the one seeing the knife, feeling her cheeks, listening to the shower—but in this crucial, pivotal moment, we’re getting absolutely none of her thoughts. What’s the point of being in someone’s head if we don’t even know what they’re thinking?

There are the writers who are perfectly comfortable writing interiority but who panic in moments of high drama. You might fall into Empty Head Syndrome, as above, imagining that Georgia would have no thoughts in the heat of the moment. Or you might feel like you want this scene to go fast, because it would happen fast in real life.

Generally speaking, inches on the page equals importance in the story (with notable exceptions, like the death in To the Lighthouse), and a corollary to that is that the more important or unusual someone’s actions are, the more we want them to stop and think about what they’re doing. So for example: If Georgia simply picks up a knife to cut an apple, I don’t need to know about why, and whether she’s done this before, and how she feels in the moment, etc. If Georgia’s going to stab her husband, though, I definitely need to know those things.

And no, this will not slow your scene down. Just like stopping for gas before you get on the highway will not delay your arrival time as much as running out of said gas would. You know what’s really going to slow this scene down? When I abandon your book because I can’t understand anyone’s motivations.

The Slack Clothesline

(Too much interiority in the wrong scenes)

Here’s what it looks like:

Georgia passed the old bank, its paint chipping. Everything in this town was falling apart. [Two more paragraphs on her thoughts about the town.] She passed the grocery store and saw her old friend Renee wheeling her cart out. Renee was a good friend, someone she trusted. [Two more paragraphs about Renee.] She circled back to her own block. If she was going to kill Michael for the insurance money, she’d need to do it soon. [Five paragraphs about her feelings on this.] She walked into the door. There he sat.

Here’s what’s wrong with it:

Take away the interiority, and what kind of scene do we have? A woman walks through town and comes home. That’s not exactly a scene of great tension and momentum.

Think of a slack clothesline. You can hang a couple of things on it, but pretty soon it’s sagging so much that everything’s on the ground. The tauter the clothesline, the more you can hang on it. In other words: A scene where someone’s about to stab someone else is a great place to hang your interiority. A scene in which someone just walks around town is not great for that (and in fact maybe doesn’t deserve to be a scene at all).

The Gas/Clothesline Combo

(Reeling back and forth between scenes of all action and scenes of all interiority)

Here’s what it looks like:

[The knife scene, followed by the walking around town scene, followed by a car chase with no interiority, followed by a scene in which Georgia sits on a bench and recalls her childhood.]

Here’s what’s wrong with it:

All the stuff that was wrong with the two scenes above, but in rapid succession!

Action and interiority do not belong in separate scenes, just like in real life you don’t mindlessly do important things and then sit still for a long time to think about your life. Rather, you decide at the messy birthday party that you want a divorce. You drive too fast because you’re upset and you hit a garbage can. You remember your fifth grade Spanish teacher as you assault the town judge. (Really, you should get control of yourself. You sound like a mess.)

Action springs from thought, and thought springs from action. We can’t silo them.

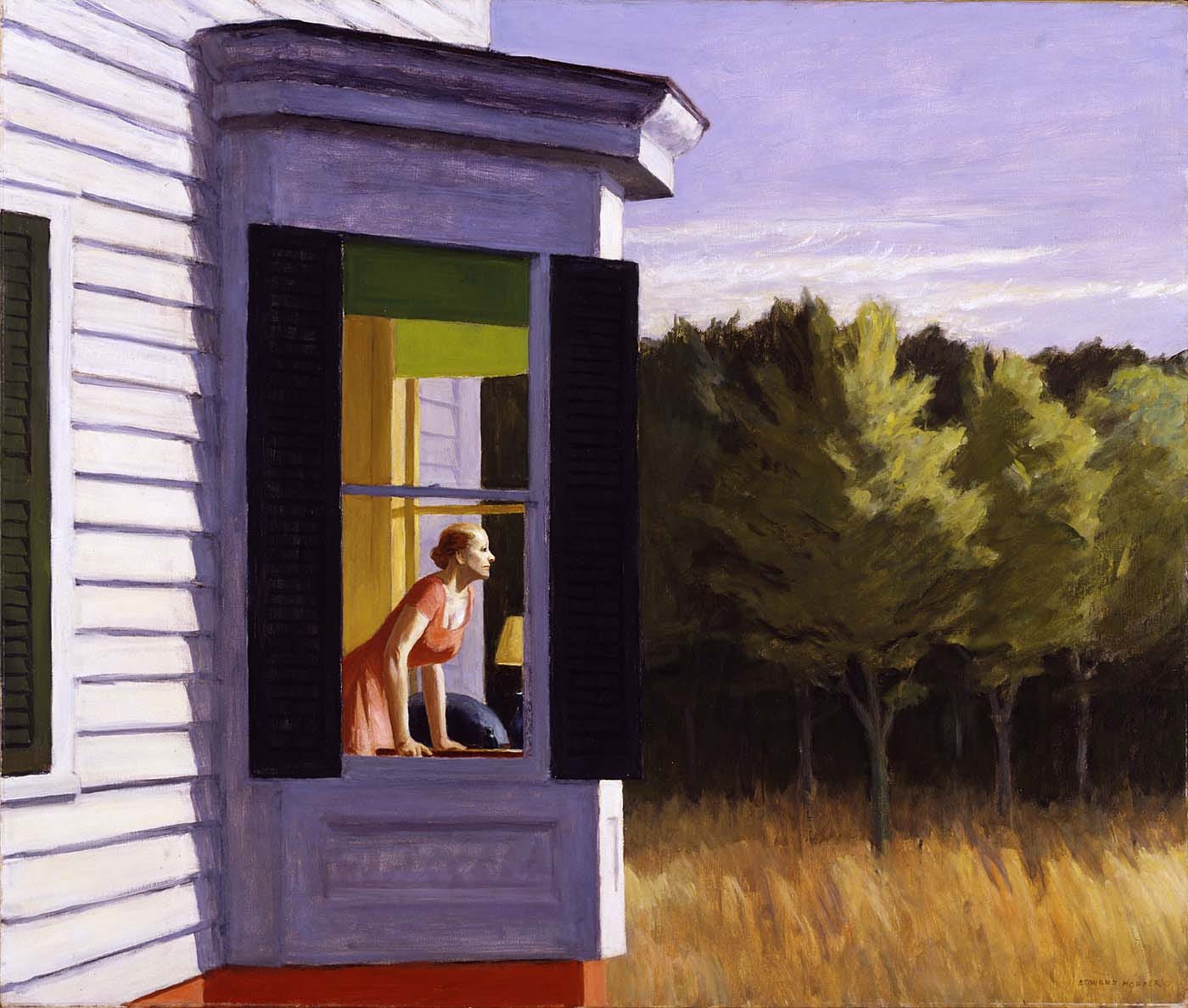

Gazing Out The Window Syndrome

(Awkwardly halting the scene for interiority)

Here’s what it looks like:

Forgetting the pot scrubber in her hand, Georgia settled her gaze out the window on the towering oak in the yard. That oak, she remembered, had been there since she moved in. The memory came flooding back to her: October, 1973, the wind blowing from the southeast, the day warm. Michael had slowed the old Datsun at the curb, saying “Look at the snow, Georgia!”…[and then we go on like this for five pages]…The door slammed, and Georgia was suddenly jolted out of her memory, which for some reason had happened in complete chronological order, with remarkably accurate detail. “Michael!” she cried.

Here’s what’s wrong with it:

This is an extreme version of the slack clothesline, but with an elaborate memory thrown into the mix. To be clear, you absolutely could go on and on for pages about someone’s memories and thoughts—but pretending that tons of memories are coming to them in real time is unrealistic, and everything reads slower if only because you’ve slowed down the actual scene; instead of just enjoying the 1973 Datsun, part of my brain is registering that we’ve been standing there at the sink a really long time.

You are absolutely allowed to just tell us stuff—within or outside of a scene—without pretending the character is thinking it in real time.

The Cardiopulmonary Trap

(Relying on breathing and heart rate to suggest thought)

Here’s what it looks like:

Michael walked through the door. He was still alive! Georgia felt her heart in her throat. Her pulse throbbed in her veins. She let out a breath she hadn’t even known she was holding.

Here’s what’s wrong with it:

We got into cliché really fast there, in part because there are only so many ways you can describe a cardiopulmonary response to stress. And while physical reaction is of course relevant and often useful, this is not a full substitute for actual thought. If you’re going to do this, use original language. Maybe pick a different part of the body! Georgia’s left ear could be throbbing, why not. And don’t let it replace any effort at interiority.

Over-Tagging Thought

(Constantly telling us that thoughts are thoughts)

Here’s what it looks like:

Georgia watched him lurch toward her. “I can’t believe he’s still alive!” Georgia thought to herself. “Wow,” she marveled inside of her brain, “there’s a lot of blood!”

Here’s what’s wrong it it:

It’s definitely sometimes relevant to state that someone is thinking something (Georgia wondered if she had a mop) but most of the time you don’t need to. You definitely don’t need to put thoughts in quotation marks or italics, moves that will likely read as dated and clunky.

How about this instead:

Georgia watched him lurch toward her. How could he still be alive? There was so much blood!

That’s not a masterpiece, but it works, and we don’t have any doubt that we’re in Georgia’s mind. (This move, if you’re interested, is called “free indirect discourse.”)

The Point of View Slip-Up

I honestly don’t know how to help writers with this one if they don’t already get what’s wrong with it.

Here’s what it looks like:

Georgia [whose head we’ve been in for the whole story] wondered if ladybugs were really all female. They couldn’t be, obviously. What if all these beetles were actually male? The thought was unsettling. Her blue eyes sparkled in the sunlight. She turned toward the house.

Here’s what’s wrong with it:

She can see her own eyeballs? Really? Neat trick!

Shallow Interiority

This is the one I see tripping up the most writers, even really capable ones. It’s important enough, and complicated enough, that I’m going to give it its own post next week. And then, probably in another post, I’m going to give you some examples of interiority done extremely well.

If you want to see that (and a picture of cake!) make sure you’re subscribed. (And if you’re enjoying this newsletter and can swing it, you could upgrade to a paid subscription and I’ll love you forever.)

(Update: Here’s the promised Part 2!)

This has been top of mind in my writing for a bit now. I’d love some recommendations from Rebecca or the community on books that REALLY nail this!

Thank you for, among other things, finally lighting up the neurons that connect my eyeballs to my cortextual interior), to what "free indirect discourse" actually means. You're the best.