Voice Lessons

Why not all characters sound alike (or at least why they shouldn't)

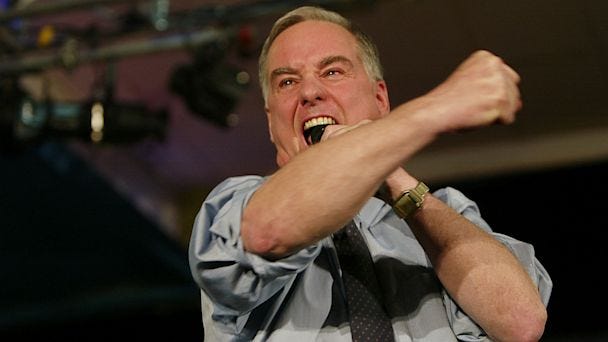

A few years ago, I was waiting for my coffee behind a guy in a business suit who felt free to lean over the counter and watch what the barista was doing. And then the most remarkable words came out of his mouth: “Make sure you get that decaf in there, guy.”

That’s honest to God what he said. I’m a decaf drinker too (I have the resting pulse of a chipmunk), and what I do, conditioned as a woman, is I order my coffee, making very sure to say “decaf”—and then, when my order is done, I go, “I remembered to say decaf, right?” Even thought I know damn well that I did. And then, once the coffee is on the counter, I say, “And this is decaf?” I know I could be more assertive, but it works.

I use Decaf Man in writing classes as an example of voice—and what voice can convey about character.

What Exactly Do You Mean By Voice?

We might use “voice” to mean narrative voice, especially when there’s a first-person narrator, or a third-person narrator with a lot of personality. Or we might be talking about the ways individual characters speak. Or we might mean commonalities of narrative voice across and author’s work.

That last one is tricky; some authors choose to sound the same from book to book, or just do sound the same, involuntarily or unconsciously. Others find a new narrative voice for each project, one that serves that particular story. Personally, I tend towards the latter—but I’m sure I do always still sound somewhat like myself. In any case, I don’t think this is anything to sweat or overthink, and I’m always flummoxed by new writers earnestly worrying about “finding their voice.” It’s like worrying about picking out what accent you’re going to speak in for your social interactions. I don’t know, just… talk?

But right now I’m talking about the first two meanings of “voice,” and particularly about the ways you might make different choices for different characters, so they don’t all sound exactly the same, and exactly like the narrator, and exactly like the author.

Factors for Differentiating Voice

You might look back at a first draft to discover that all of the characters sound pretty much like you. And that’s fine. But one of your rounds of revisions can involve making solid choices about who is going to talk in certain ways, and then going back through to make it true.

Here are some factors to consider:

Formality

Does a character say “maybe,” or “perhaps”? “Hey,” or “I beg your pardon”? “Can’t” or “cannot”? Do they speak in complete or incomplete sentences (“Are you alright?” versus “You okay?”)? Does a character use slang? (And if so, is it pretty standard-issue and unconscious, or performative?)

Length of sentence

Some people ramble. Some get to the point. Some sound like the lovechild of Hemingway and Tarzan. Some people shoot out incredibly long and complex but grammatically correct sentences. Some leave a never-ending trail of incomplete ones.

Emphasis (italics, repetition)

Without overdoing it, you might have a character talk like this, and they might get really excited about things.

Or they might repeat things for emphasis, just for emphasis, which could be nicely and subtly—subtly!—telling of character. In real life, people repeat themselves quite a lot—and this can be redundant and deathly on the page. But used just for one character, and/or used as a sharp tool, it can be incredibly effective. Consider Hemingway’s Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?

Punctuation

Some of my students recently noted that Mrs. Croft in Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Third and Final Continent” has only one line of dialogue that doesn’t end with either an exclamation point or a question mark. That might be irritating elsewhere, but it’s perfect for that particular character. Example: “Sit down, boy!” She slapped the space beside her.

Tics

We all do have them. Think of your teachers and professors, and what you used to do to imitate them. I had a wonderful professor in grad school who would end just about every sentence with a drawn out “Noooo?” I dated a guy in college who needed to find three examples for everything. I never told him he did this, because it was too much fun to wait and see if he’d do it. He always did it.

Politeness

Decaf Man did not have this going for him. Some of us do.

Swearing / crassness

Not all people swear, and not all people swear in the same way. I’ve gone through my own manuscripts before deciding who’s liberal with an F-bomb, who expresses disbelief with “Jesus,” who says “your sorry ass,” who swears creatively, who comes out with an old-fashioned “damnit.” The latter is something I don’t think I’ve ever said myself, which means it’s not what would instinctively come out as I write; but it’s exactly right for a certain character.

Do note that a little bit of swearing goes a long way on the page; if you get anywhere close to the amount of swearing that some real people do, you’ll read like a seventeen-year old who just discovered you were allowed to be edgy in Creative Writing class.

Figurative language

Some people speak literally, some use stock or cliché similes (“It hit me like a ton of bricks”), some are constantly seeing and expressing connections between unlike things, some use figurative language that seems a part of their dialect and/or worldview (George, in Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men: Well, you keep away from her, cause she’s a rattrap if I ever seen one)… I’m delighted to discover that someone wrote a whole scholarly article on An Analysis of the Metaphorical Speech of H. Ross Perot.

Ornamentation

Some people accentuate their speech with descriptive adjectives, with poetic description, with lovely words. Make sure that this is a character choice, though, and not a matter of you, the author, constantly trying to pretty up your language.

Signature words

Certain words might only belong to one character. I do NOT mean a catchphrase (like Little Orphan Annie’s “Leapin’ lizards!”) but a subtle word with resonances. In my novel The Hundred-Year House, I realized in a late revision that I had the word “poor” everywhere… a subconscious inclusion, but fitting for a novel that was in many ways about class. I went back through and took it out for all but one character, and then let that character say it even more often. It was sentences like “I don’t know what that poor girl was thinking” or “and think of poor Jennifer, out there with that husband.” Those are absolutely not examples from my book, because I’m not going to go hunting for them right now, but that was the gist of it.

Hesitation or directness

Some people get right to the point; others beat around the bush. There’s a huge difference between “Can we expect you at the party?” and“So, are you—will you be at the party, do you think?” and “Are you, like, coming to the party?”

Too much hedging and hesitation, and it becomes painful to read. But when there’s none, especially when you’ve given a character a lengthy monologue, it’s no longer believable as human speech.

Clarity

Some people are able to express themselves clearly and easily. Others might speak elliptically, or have trouble saying what they mean. Consider the difference between “I heard that there’s a plan for an improved highway connecting Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan” and “I saw this thing where they’re going to build a road. Like, between Wisconsin.”

Grammar

Grammar and syntax can be affected by education level, region, racial context, class, fluency, and intention. To what extent does a character have a mastery of the grammar of those around them, and to what extent do they care to match it?

Also, note that many of us write a lot more properly than we speak. (I would never write “a whole nother” (except right now), but I say it all the time.) If a character constantly speaks with perfect grammar, that is an authorial choice—and depending on the character, it might not be a believable one.

Vocabulary

Similar to the above… There’s the question of how many SAT-level words a character might use, but you can also consider regionalisms and life experience. Consider the difference between a character who talks about going to the “john” versus one who’s headed to the “potty” or the “crapper” or the “restroom” or the “little girl’s room” or the “powder room” or the “latrine.” Having an American character talk about “queuing up” might suggest either time spent abroad or pretension, or both. When your character says “anyhoo,” it tells us a whole lot.

Humor

Even in a comic novel or story, it’s a mistake to make all the characters funny, and to make them all funny in the same way; it becomes quickly clear that it’s just the author’s own sense of humor coming through. Pick who is funny, and in what way they’re funny: sarcasm, striking figurative language, off-color comments, brutal honesty, silliness, puns (please don’t), flights of fancy, mockery…

Accents

(And I’m including not just regional and foreign accents but also speech impediments, unusual pronunciation mannerisms, drunkenly slurred speech, etc. here too.)

This one is tricky, which is why I’m putting it last. You want the reader to hear the voice as you do, but transcribing an accent phonetically onto the page can be at best distracting and at worst offensive.

Phonetic spellings often reek of the 19th century, and can evoke the racism of books in which phonetic spelling suggests a connection with illiteracy. (Think of books in which the word “was” is spelled “wuz” only for the Black characters. There is literally no other way to pronounce that word. So what on earth does that spelling accomplish? Or think of the antisemitic portrait of The Great Gatsby’s Meyer Wolfsheim and his “gonnegtions.”)

It’s not that you can never spell a word differently to show the way someone pronounces it. I’ve represented a German accent by put a character’s W’s as V’s (“vhat do you mean?” etc.), but then found it so annoying when there were too many in close proximity that I bent over backwards to give her words without W’s. It felt like a strange improv game.

What’s just as effective in most cases is to rely instead on syntax. Consider a southern waitress asking “Y’all fixin’ a eat sumpn?” versus “Hungry, darling?” or, perhaps, “Hungry, darlin’?” The latter two are far less distracting but still evoke her accent.

You might suggest the accent of someone newer to English through syntax as well; your character might say things like “It wonders me” or “We find three dog.” (Do research the mistakes a speaker of a specific language would make in English. YouTube can be a great source for this kind of eavesdropping.)

A child might say “Have fun at Texas!”; a small child might say “I pick you up,” meaning the opposite, or “Mommy go store” (but certainly might say “breafakst” or “pasghetti” as well). My nephew at age 3, was tried to tell me that his guinea pig, Squeaky (pronounced Ee-ee) had died; what he said was “No mo Ee-ee. Ee-ee uppy hi Jesus!” If I were putting that in a book, I’d render it exactly as I did here.

Do note that as with “darlin,’” above, I think it’s significantly less distracting to use commonly accepted casual spellings like ‘cuz, gonna, kinda, anyways—the ones you might type in an email.

After the pay wall, as a thank-you (OMG thank you!) to the paid subscribers who help justify the time I spend on this newsletter, you’ll find the game I have my students do as an exercise voice. I love it because it’s appropriate for both the most beginner and the most advanced writers…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to SubMakk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.