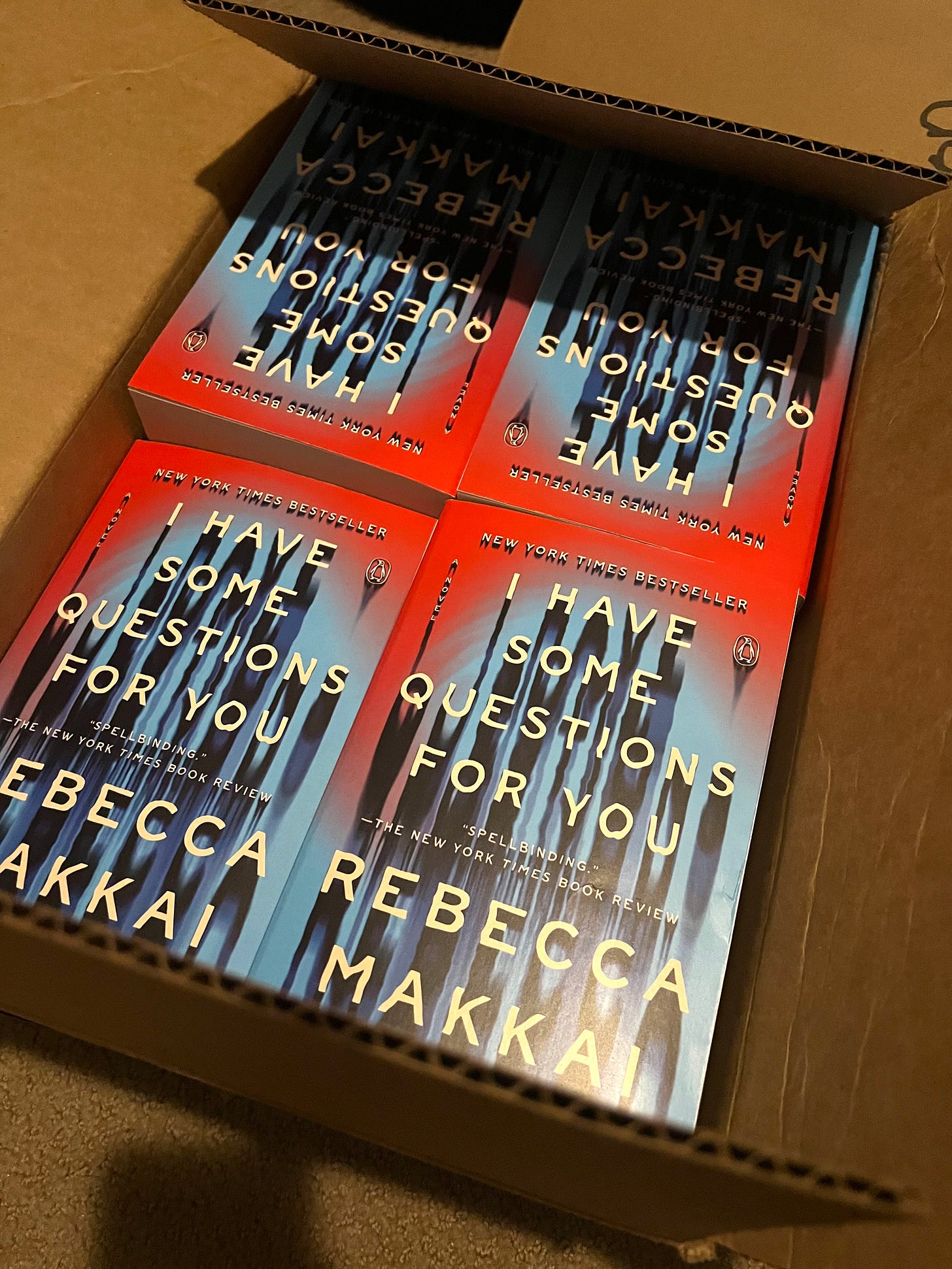

My paperback for I Have Some Questions For You is out today (did you know that all books come out on Tuesdays?), and I’ve realized that the paperback thing is not entirely intuitive to readers. So I’m here to explain it all.

What are paperbacks?

Beyond the obvious (the floppier cover), they’re bound with glue rather than with the stitching that usually holds a hardcover together. This makes them flimsier and more likely to fall apart 20 years later, but they don’t hurt as much if you’re reading in bed and you drop one on your face.

When do they appear?

If a book originally came out in hardcover, the trade paperback usually comes out a year later. An exception would be if the book is doing extremely well, and they keep it longer in hardcover (for which the publisher makes a better margin). For instance, All the Light We Cannot See stayed in hardcover for three years. Another exception, a sad one, would be a book that really underperformed in hardcover and so the expected paperback is never issued.

Wait, what about Fabio?

Right, so there are plenty of books that appear as paperback originals. For one thing, there are “mass-market paperbacks,” which are smaller in surface area and usually printed on cheaper, acidic paper. These are the ones you might find in an end-cap or spinner rack at the pharmacy. Often these are romance novels or mysteries or thrillers, but not always.

If you read literary fiction, you’re more likely to own a lot of “trade paperbacks”—larger in surface area, acid-free paper, sold in indie bookstores and elsewhere but probably not at Walgreens. And while many trade paperbacks are reprints of hardcovers, there are plenty of trade paperback originals (as in, it never came out in hardcover) for all kinds of books—including commercially-aimed romance/mystery/thriller books and lighter novels, but also including books from smaller/independent presses that aren’t up for a two-edition extended rollout, and books from larger presses where for whatever reason, the publisher felt better taking one shot than two.

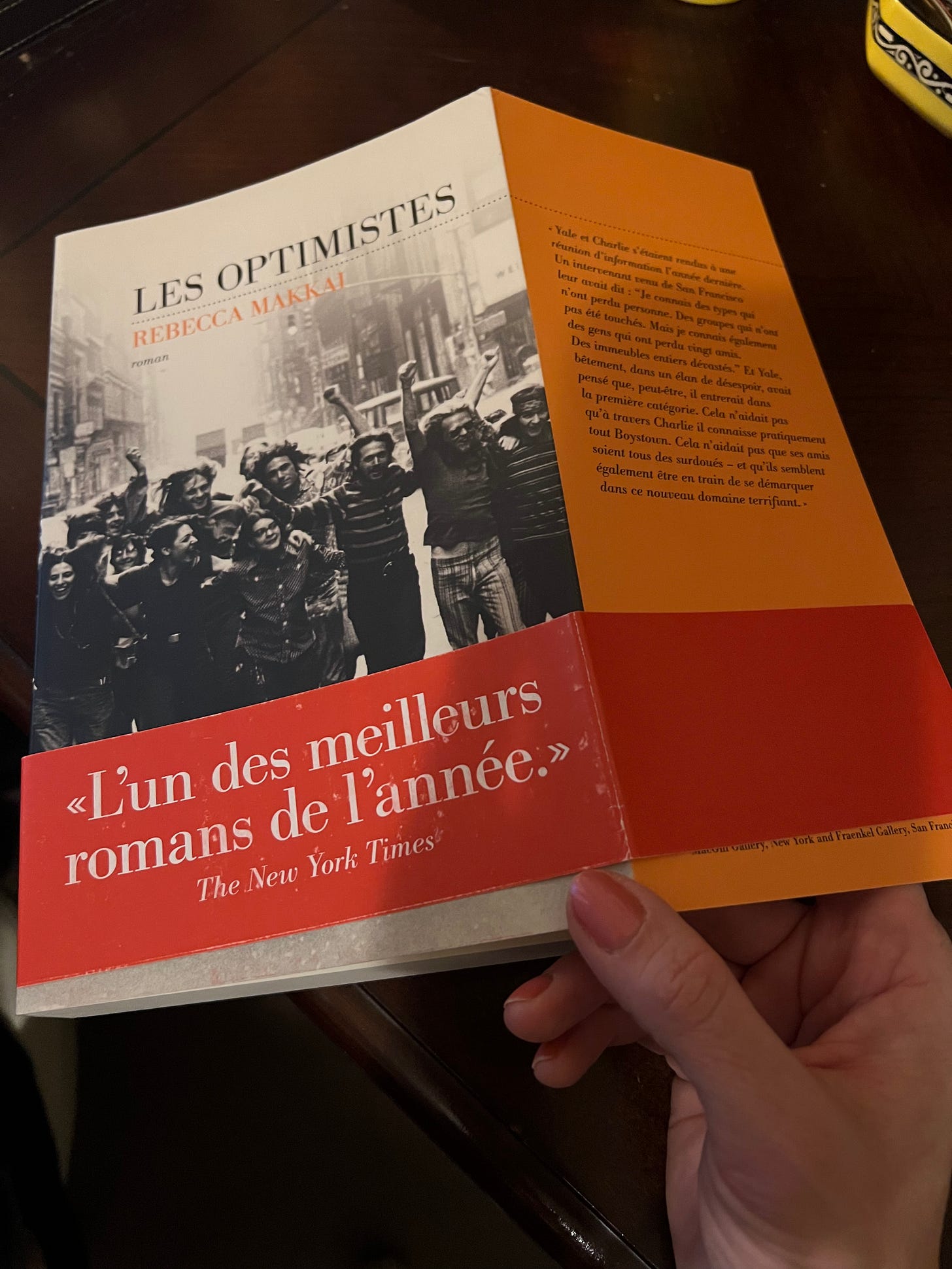

Many other countries have gone to one high-quality paperback and dropped hardcovers almost entirely. These books often have nice, sturdy covers, “French flaps,” and thick paper with beveled edges.

Is it the same book?

Yes, with the same pagination and everything—but usually, in the preceding year, people have gotten in touch about any typos or factual errors, and so those will likely get fixed in the paperback. For instance, I had three different people write to me after The Borrower came out to inform me quite angrily that the dog on the Hush Puppies shoe box is a basset hound, not a beagle—so that is fixed in the paperback.

Who thought this was a good idea?

Okay, a very brief history of the paperback.

In the mid 1800s, as steam-powered presses made printing easier, several British publishers started producing cheap “yellow-backs” (on cheap yellow, or yellowing, paper) and selling them in railway stations. These were all stereotype reprints of existing books, with rights bought from the original publisher.

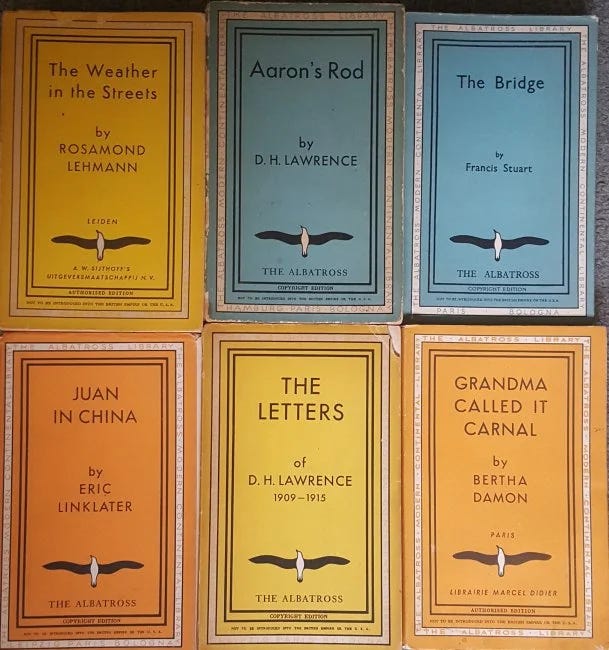

Albatross Books, a German publisher, was the first to go with a standard look and a notable logo and the shocking new sans serif font. This was the early 1930s, though, and then 1930s Germany happened.

Allen Lane, a British publisher, launched Penguin Books in 1935 and basically copied all of this, including a bird logo. His success inspired Pocket Books, Dell, and Bantam in the US. They eventually started republishing more recent titles, and they got really into those spinner racks. During WWII, the Armed Services distributed 122 million paperbacks to troops.

In 1950, Gold Medal Books started publishing paperback originals—which is when we started getting pulpy westerns and romances and incredible books like these ones that I found this summer:

A lot of writers who used to write for pulp magazines moved over to writing entire novels about, uh, nude men with thighs but no legs? This is why “paperback writer” was a specific job as of the Beatles’ 1966 song.

Trade paperbacks came on the American scene around 1960, with publishers retaining the rights and republishing the books themselves, rather than selling the rights to a paperback press. (Often, the paperback is put out by a specific paperback imprint within the larger house. So my books bear the Viking logo in hardcover, but the Penguin Paperback logo in paperback. Vintage is the main paperback imprint for Random House, and so on.) That’s where things stand now, with Colleen Hoover having mostly replaced the aliens and pirates and naked clones.

So why do they still make hardcovers?

As noted above, it’s a better margin for publishers: Hardcovers sell for twice as much, but don’t take twice as much to produce. They also take up more room in a store, which makes them more noticeable on a shelf or table. And because not every book comes out in hardcover, it’s a signal from the publisher that this is a book to take seriously. A hardcover is more likely to be reviewed, for one thing.

Do paperbacks sell more than hardcovers?

Currently, according to Statista, hardcover books are about 30% of the market, paperbacks are about 38%, ebooks have fallen to about 12%, and audiobooks (the fastest growing sector) are up to around 12%. (If you notice that doesn’t add up to 100%—the rest are board books, “special bindings,” and “other,” which I assume either means comic books or books printed on fruit leather.)

Of course, that doesn’t mean this is how the sales of any individual book will break down. I can tell you, for instance, that almost six years in (!), The Great Believers has sold more than twice as much in paperback as it did in hardcover. (The audiobook has sold about as much as the hardcover did, and the ebook has sold almost as much as the paperback.) If a book has a long life, most of that life is in paperback. Think about how many more paperbacks The Cather in the Rye has sold, versus how many copies it originally sold in hardcover. In contrast, think of the political books issued in hardcover, bought in bulk, and then complete forgotten.

Why does the cover sometimes change?

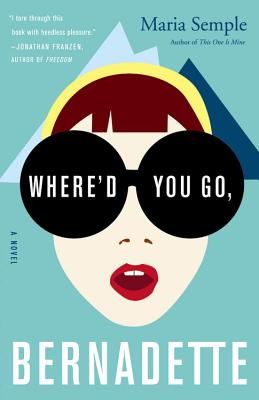

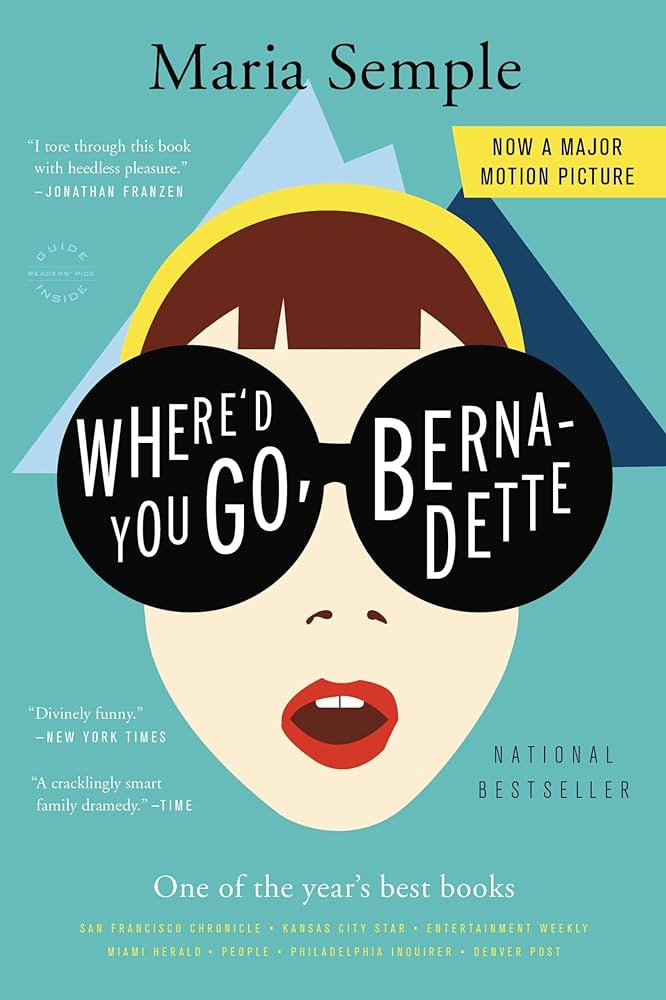

If a book does spectacularly well, they won’t change the cover much. Witness the hardcover and paperback versions of Where’d You Go, Bernadette:

But if sales were only okay, or less than okay, a redesign might help a book appeal to a new, different audience. Here are the hardcover and paperback versions of my second novel, The Hundred-Year House. It sold respectably well in hardcover, but the redesign helps signal that the book is kind of gothic/about ghosts.

Later on, a cover might change for an anniversary edition or special edition or because it got made into a movie and now they need to ruin the book by putting Adam Sandler on the cover.

Are you going on tour for this? Why?

Yep. And here’s my schedule:

I'll also be at the Ennis Festival in Ireland in early March, followed by events in Barcelona and Madrid, and then the Literary Women of Long Beach Festival on March 9th.

I’m very lucky to do this, as not everyone tours for a paperback. It definitely feels different than the hardcover tour—less nerve-wracking, for one thing. A year in, people are more likely to have already read the book (which means more specific questions at the events), but might be bringing their book club to the reading. Touring again means you’re bringing the book back to people’s attention, at least in the communities you visit. There might be more press, and if nothing else it’ll be all over the bookstore’s social media.

And then here’s what it took me a few books to figure out: The main thing about a book tour isn’t the audience, as lovely as they are; it’s making friends with the booksellers.

What’s up with Target?

They’re a pretty big mover of paperbacks, and (alas) in some communities, the only physical way for people to browse books. They have a small selection, and this will be the first time a book of mine is there. Although I’d always prefer that you buy my book from an indie bookstore, Target is in fact my spiritual home so I’m more than okay with my book hanging out there. The decision to carry a book is not up to each individual Target, it’s up to the Target Book Decider, which is probably not that person’s real job title. (Same, by the way, with airport bookstores, almost all of which are Hudsons even if they sometimes have a different name. I love it when people text me, like, “The Anaheim Airport bookstore loves your book!” but really, it’s not that one airport or store; Hudson either carries and highlights a book or doesn’t.)

What’s the best way to order a paperback?

(Best for the writer and the literary ecosystem, that is.) By far the best way is to preorder (before the book is even out) from an indie bookstore, or to get it right when it comes out. And you can do this online if you don’t have a local one. The second best is to get the book from said indie after the pub date. (Tied with these two—but this isn’t about paperbacks—would be preordering or ordering the audiobook from libro.fm, which gives your money straight to the indie bookstore of your choice, or ordering the ebook via Kobo, which does the same.) The next best is a larger brick-and-mortar store. The next best is getting your wonderful local library to order it. The next best is funding Jeff Bezos’s penis rockets.

The next best is buying some weird pirated version. The next best is walking into a store and actively talking everyone out of ordering it. The last best is joining Moms for Liberty and destroying the fabric of our country and its free speech and educational system.

Iconic ranking of "Best ways to order".

I love that you took the time (lots of it?!) to write this guide to paperbacks! Perhaps now I'll have to explain to one fewer person why they have to wait a year to get a paperback edition of that new novel, or what we mean when we say "mass market." Enjoy the paperback tour!