Thank you all for your questions about I Have Some Questions for You! Thank you for not making a joke about the title as you asked them!

We’ve got two sections here: spoiler-free and spoilerific. The spoilers are well-labeled, so don’t fear about reading on if you haven’t finished the novel yet.

I couldn’t get to absolutely everything, but I tried to pick specific and representative questions. And I had a lot of fun answering the spoiler questions… I never usually get to talk about the end of the book!

Spoiler-Free Questions:

At what point in your writing career were you able to support yourself by writing alone?—which I hope is the case, otherwise the rest of us are doomed. (Someday, I'd love to be able to spend all my time writing books, and I'm curious what it takes to get there.) — Marisa

While technically I don’t support myself fully by writing, at this point that’s by choice; I love teaching, and so I do a lot of it. But after my fourth book (The Great Believers) I was making enough from writing itself that I could have supported myself, at least for the time being, just on my publications and speaking gigs; and I’m incredibly grateful that this continues. It’s not terribly common, but I also don’t love that in our effort to make people understand that it’s rare and difficult, we spread this narrative that absolutely no one can make a living as a writer, or even in the arts in general. That’s not true.

Here’s the less romantic part: There’s a whole lot of the business of being a writer that is not writing. A very successful writer could hole up and not emerge except for a tour or two , but even so, the more successful you are, the more just… stuff there is. And if you want to be a good literary citizen (blurbing books, reviewing, being in conversation with writers visiting your city, teaching at a conference, writing letters of recommendation, judging prizes, doing good stuff for literacy organizations, etc. etc. etc.) you’re going to be incredibly busy, as I am, with things that aren’t just writing. The good news is, those are things that give you a literary community—which means happiness and friendship and support. And if you ever have a book that flops (or that you need to scrap) those teaching/conference/lecture gigs might still be there to help make ends meet.

Do you find your theatre training helps your writing? When I’m writing dialogue I have to block out everything. Like I have to have the set, and I’m telling folks “you’re stage right, he crosses down left.” — Maria

Maria is asking this because she’s a college friend and we did theater together. If I really wanted to embarrass both of us, I’d post a photo.

The answer is a huge yes, to the point that when I’m asked what writing advice I’d give high school or college writers, the first thing I tell them is to get involved in theater. You get to live inside one story for weeks on end, overthinking character relations, motivations, energy, etc. Plus you’re much less likely to write bad dialogue if you’re trained in making the words actually come out of your mouth.

My first drafts often look more like scripts—tons of dialogue and blocking—with interiority coming later, and it sounds like that might be the case with you, too. It might not be the very best theater side effect, but I can live with it. It’s like scaffolding for a scene.

I thought the lists of "the one who..." throughout the book were so impactful. They were all anonymous except the one reference to Martha Moxley. Why did you choose to break the format and use the victim's name in that one instance? — Ellen

I didn’t consciously realize she was the only one I named! (I did name some Hollywood cases by name, but those are definitely in a different category.) Those lists are a mix of real stories (some highly recognizable, some less so) and ones that I completely made up. If I had to recreate my writing process there, I’d guess that it was because this was much easier shorthand than “the one where the famous politician’s distant cousins said they were watching Monty Python but it might not be true, and also the golf clubs might have belonged to the tutor” etc. etc.

My question is about voice: What were your thoughts about developing the voice for this book, and if you have any comments about voice in suspense fiction generally (my opinion being that many thrillers are rather flatly voiced, so the freshness of yours, even aside from great plot and incisive cultural commentary, was one of its best aspects.) — Andromeda

Weirdly, I don’t dwell on voice very much at all. Maybe it helped in this case that I never thought of myself as writing suspense fiction, but writing a realist story grounded in character. I’m always flummoxed by the descriptor “character-driven,” but I think what it ultimately means is that you’re leading with a realism of character (what would a real person think or do, even in a surreal situation) rather than leading with what your plot needs.

All of that said, I do start my thinking with plot, and then I work backwards from there to reverse engineer the character who would be most susceptible to those circumstances.

I had a hard time getting a handle on Bodie and her. voice early on, and things didn’t really click for me until I had her name (I went through a bunch, and she was a failed Casey for a while) and her occupation.

(Speaking of her occupation: This is so cranky and tangential, but it’s been driving me nuts when people write up the book in reviews calling her a true crime podcaster. Her podcast is about women in Hollywood! It’s about Rita Hayworth! You only want it to be a true crime podcast!)

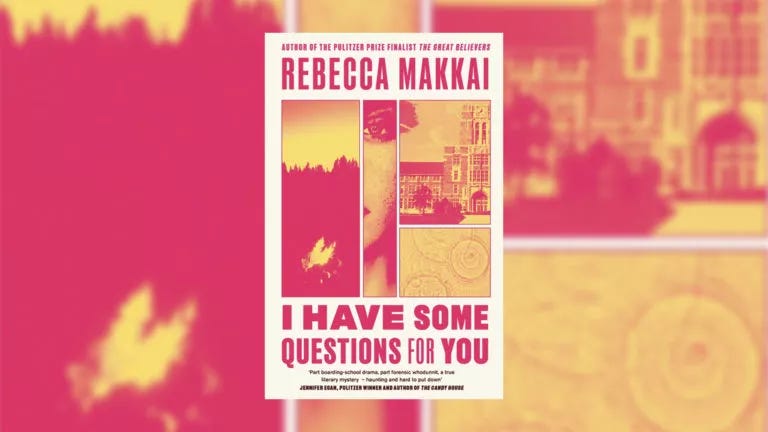

The cover, the cover… it has a very striking and harrowing color scheme and typeface. I am usually agnostic about most of the covers of my books. Did this one suit you? Did you have the opportunity for a solid contribution to its looks? Many readers think authors have total veto control over titles, covers, design etc. but that’s not quite the case, is it? Or maybe I’m the only one who does not! — Jacquelyn

I love that this cover reads as abstract but then, once you know the book, might read as blood in the water. I actually do have veto power, but there’s a point at which you’d be driving your editor and the art department nuts, so you need to exercise that right with restraint. We’ve definitely gone back to the drawing board a few times with other books, but for this one, we were always working with a version of this cover—in part because since it’s such a long title, it was always going to be text-centered. We just kept adjusting the colors and font and spacing. There was one lunch at which my agent and I and several people from Viking had print-outs all over the restaurant table, staring at different configurations until we couldn’t tell them apart anymore.

Here’s my UK and world English cover, by the way; totally different but I really love it.

Is there any possibility this story will become a streaming series? It’s got all the cinematic hallmarks of a fantastic miniseries! (Follow up question… do you have a dream actor who you’d love to see cast as Bodie?) — Tanya

It has been optioned for a limited series! That’s just the first step, and nothing is certain until you’re actually eating the popcorn, but there’s some really amazing talent and energy around it. My dream Bodie is Lizzy Caplan. She had fallen off my radar between Mean Girls and Fleishman is in Trouble, and I don’t think I’m alone in that… It’s perfect that she’s someone we tend to think of both as a teenager and as a 40-year-old.

How do you plot out/ keep track of your work/characters/multiple storylines? I was fascinated by the complexity of your characters, especially the second half. Do you make charts? Excel spread sheets? Index cards? Do you print out everything and make notes? I’m writing a more complex book right now and despite doing everything I mentioned above, going into Word and scrolling is part of the awful process! (On second draft with editor, so it’s no longer in Scrivener.) Just curious about your process because I loved this book so much! — Hayley

Oh God, anything but Scrivener for me! I think it’s made for organized people, not me and my ADHD brain. I write in one giant Word doc, but then I do have a lot of ancillary documents—timelines, calendars, maps, research, and eventually an outline. Later, in revision, I’m more likely to have index cards all over my floor.

Mostly I find my place in the Word doc by doing Control+F on an unusual word or phrase that I know is in the scene I want to find. (I do have a highly specific memory for my own writing.) This usually means I’m doing Control+F on “penis” or something, like the classy grownup I am.

Is everything we know about Judy Garland all wrong? — Mark

Probably!

Here There Be Spoilers…

Turn back while you still can!

I have a nerdy punctuation question - why didn't you use quotation marks in Omar's podcast interview (Part 2, Chapter 6)? — Dena

I’m not sure that was a conscious decision, but what fits about it for me is that I wanted to find a way to give Omar a voice almost directly, despite the fact that his voice is fundamentally silenced. (That was a big, troubling paradox of the writing process for me.) I figured out how to basically give him his own chapter without breaking Bodie’s narration, and it tracks for me (now, in retrospect) that his dialogue isn’t in quotes but is presented directly, as if he’s the one narrating the chapter (even though technically, he isn’t).

I really enjoyed the book, and as someone who's writing a crime novel with minimal violence in the present (which is how I classify yours, I could be wrong), I wanted to know if you felt like you needed to increase the present-day action for Bodie to up the tension, or if, for you, it was more about the journey as it unfurled and letting that be what it was? — Alex

I was happy writing a realist novel, one that had its own energy but that didn’t ramp things up to thriller pacing. Things pick up as you go—you might notice that the chapters get shorter toward the end, which helped me to speed up the pace—but I never put Bodie or anyone else in real danger in the present day. I don’t think I could’ve done that with a straight face, like had someone threaten her with a knife and be all “You know too much! Watch your back!”

(It’s funny, I have never called the book a thriller, and it doesn’t say thriller anywhere on the book, but then of course there are people online being like “This book was advertised as a thriller, and it failed at being a thriller, one star.”)

Here’s a twofer:

Did you ever consider having Mr. Bloch appear in the present day section? And how early into the book did you make the decision to structure the novel as addressing him? And was he actually the killer at any point in the early drafts? (Sorry, that's three questions, but they are all Denny Bloch-themed!) — Nina

How did you reconcile leaving Denny out there undiscovered? I started to think he is the unresolved loose end standing for all the men who always get away with it, but then thought that was terribly moral-judgment-y of me. What are your thoughts? — Caroline

I never felt like bringing him back in the present and letting him appear onstage, as it were. I was careful about who I let speak: essentially, Bodie, Beth Docherty, and Omar are the ones who really get to tell their stories. Maybe it was a craft decision (an inversion of a Lolita-type narrative in which it’s the offender’s voice we hear) or maybe it was personal (as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse I just wasn’t up for, or interested in, letting Bloch speak), or maybe it was both.

I did leave him relatively unpunished at the end, but with everything pointing toward his demise—the other young women’s narratives emerging, Bodie pretty much vowing to go get him.

As we’ve talked television, the question has come up of what a second season would look like… I think it would likely have to do with both Denny Bloch and the school itself facing repercussions, and more secrets coming out, as well as Omar’s continued legal appeals

No, I never considered having Bloch be the one to do it… I knew it was Robbie from the beginning. And the book was addressed to him just about as soon as I began actually writing (which was after thinking about the book a lot for a couple of years).

In this book, you're handling a lot of information, secrets, memories etc. Much of the mystery/suspense of the novel hinges on when and how information and secrets are revealed. Withholding too much can kill a story, but so can giving too much too soon. How did you negotiate this challenge? — Haili

Although this is the first real mystery I wrote in any literal way, that rate of reveal didn’t feel much different from my previous novels. There’s always something I can’t wait to tell you, and I love misdirecting readers until I’m pretty sure they won’t see something coming. (For Great Believers readers, the big moments there would be the Charlie reveal, the Roman reveal, and the late Julian reveal.) I wish I could say something more articulate about this, but it’s really instinct, and putting yourself in the reader’s shoes so it’s clear to you what they know, what they don’t know, what they’re probably thinking, where they’re looking.

Speaking of which…

The way you directed our suspicions away from Robbie was brilliant, and I have a question related to that. While I was reading it, I briefly thought I'd been so clever and figured out who the killer was: Geoff. When Thalia asked him to make the fake ID shortly before she was killed, I thought it was going to turn out that he'd met up with her that night and was involved with her death, if not directly responsible. I'm curious, was that suspicion something you intended to create, knowing how people read mysteries, or was that just my brain being ridiculous? :) — Hannah

Oh definitely! I also put enough crumbs out there that you might think it was Dorian (Thalia is looking for him the night she fights with Robbie in the bar, so maybe they had something going on) or even Fran (who had master keys and the ability to roam the campus at night). I knew that mystery readers are always looking for the person you least suspect, and so they’d be looking for people outside of the suspects Bodie runs through in her head.

I was so proud of myself for figuring out faster than Bodie that Denny Bloch had been having an affair with Thalia that I think it made me less likely to consider anyone else as a suspect, which made me particularly blindsided by the reveal of Robbie as the killer. Was waiting so long to reveal Denny's predation a deliberate choice to mislead the audience, or am I both smarter and dumber than I think I am?

Also, how much fun did you have dropping blatant signs as to who the actual killer was (including the woman wearing a shirt that literally says "the boyfriend did it") knowing that the reader would almost certainly not take them seriously? — Tom

Related to the above: The more I could hide Robbie in plain sight, the more I could talk about how there was suspicion on him, the more I could let Bodie picture him as the killer, even though she believes it’s an impossible scenario, the more I was ruling him out for readers. And giving you plenty of (real!) things to figure out about Mr. Bloch definitely worked as a diversion.

I found the Robbie Serenho reveal to be so surprising, especially after the chapter of Bodie's speculation and she literally splits his consciousness. The "reveal" chapter of Robbie is equally good. Which one did you write before the other? Did you have to come up with his alibi after discovering he was the killer? TL;DR - how did you sequence the writing and conception of the two chapters? — Patrick

I knew from the beginning that Robbie did it, and I knew where and how, and I knew about the bike mud spatter that would give him away. I have friends who are full-on genre mystery writers, and almost of all of them say that you should know from the beginning how the crime went down. (Or at least that you’ll save yourself a lot of time and headache if you know.)

Part of the reason the “Robbie splits himself in two” chapter is there is so that you’re able to picture that scenario and imagine the kind of violence and motivation involved, even if the crime actually occurred in a different place and a different way. I knew as I wrote that chapter that I was talking about the right guy in the wrong scenario.

And let’s end on one about the ending:

“Below me and above me and in the woods stretching thick and endless, their leaves made sugar out of nothing but light” is beautiful, perfect, hopeful, and inspirational. How did you decide on this ending? What else were you thinking about and tying in, to include this imagery as your summary? — Heidi

As I wrote in my acknowledgments, I was listening to a craft talk from the poet Kaveh Akbar at the Tin House Writers Conference when he said something about photosynthesis being the way a tree turns light into sugar that hit me immediately as both deeply beautiful and as an image I needed to use.

I’m never consciously trying to summarize or moralize at the end of a book, but I do put an enormous amount of thought into the landing point and also the sound and rhythm of the language there. I do feel like at the end of anything, I switch from being a prose writer to thinking like a poet. So it’s appropriate that a poet inspired my ending.

In the novel as it continues in my imagination, public pressure has increased, Omar had gotten a new trial and he has finally been released. After a settlement from the state of NH, he gets his technological bearings, moves to a state with fewer memories, (Massachusetts, I think) and starts his own podcast, "Exonerated" - interviewing one by one the hundreds of falsely imprisoned and later freed formerly incarcerated men and women. At some point, Bodie is a guest on his podcast, (maybe a producer of it?) [I don't dare look up whether there is already such a podcast - there probably is, but for the sake of this conjecture, let's say I came up with it.] As a formerly (but totally guilty) incarcerated person, I need Omar to be free, at least in my head.

Yeah.... pictures of our mutual theatre experience are mutually destructive. Don't start none, won't be none.😆