When I’m reading student work, my most common marginal notation is “?” Or, sometimes, “??” or even “???” I try very hard to limit myself to three. Sometimes I’ll write “I’m lost here” or “I’m totally lost” or “Wait, how many people are in this boat?” or “I have no idea where they are” or “Who is talking?” or “How much time has passed?” or “Huh???”

The thing is: One of the hardest feats for a writer is to orient the reader (using only words and punctuation!) to the world and context and circumstances of the story. And yet if you aren’t reading a lot of student work, or a lot of lit mag submissions, you likely have no idea that it’s hard at all. Because everything you read (presumably, published work) orients you to the situation in what feels like an effortless way. If you’re reading a published book and you’re lost, it’s quite likely your own fault; you haven’t paid sufficient attention, or you misread something. If an editor is reading something unpublished and is lost, they’ll assume (probably correctly) that it’s the fault of the manuscript; and they’ll toss it aside.

It’s the quickest of dealbreakers—why would I keep reading what I don’t even understand?—and yet it’s the number one issue I see in promising student work, in submissions for classes or contests, in stories languishing in various rejection piles.

So what’s going wrong? Usually, it’s one of the following four problems:

I can picture it, so I assume you can picture it.

I once received a student story in which people were hanging out in pods of some kind, in what was maybe a lab of some kind, in some kind of indeterminate space. (I only share examples from student work with permission, except in this one case, because this student, no matter what advice I gave him, would send me point-by-point rebuttals and was exceedingly rude in every possible way.) When I asked the writer where these characters were, he told me, as if I were incredibly dense, that it should be obvious that they were in outer space. Because on page seven, they are looking at the stars. I pointed out that people can also see the stars from planet earth. He continued to think I must just be a really bad reader.

Usually the writer isn’t this obstinate, but it can take an outside reader to point out that you haven’t explained everything you think you’ve explained. And we aren’t mind readers.

I’m intentionally going to disorient you, because it works well in film.

I give you two people in a car, having a fight about their marriage. You assume they’re alone in the car. Then a couple of pages in, I zoom out and whoa, they’ve actually been in the backseat of a cop car this whole time!

You’ve seen this a million times in movies. I show you something, then we shift the frame and you see the full picture and haha, you’ve been tricked, how fun. It can work on screen, even if 90% of the time it’s still really annoying. But it works because despite that frame shifting, we’re still fundamentally oriented. We’ve been anchored the whole time in the visual and auditory world; we’re not doing that work ourselves. But the written word is different: Minus the literal physical picture and the soundtrack and the actors’ faces, all we have is confusion, plus the sense that you think you’re reallllly clever. Not a great combination.

Plus: In fiction, we’re meant to have access to characters’ thoughts, not just look at them. And those two people in the cop car? They knew they were in the cop car, that whole time. It never left their minds. So why is that information being kept from us?

I’ll fill you in, but really really slowly.

This is different from the above, and more in line with the first problem—because the author often doesn’t realize the reader doesn’t have the full picture.

So, on page 2 I tell you that Amelia is sitting alone, thinking about hiking in the woods. Then on page 4 I mention that Amelia has red hair. You’d pictured black hair, so now you have to re-picture it all. Then on page 8 I mention that Amelia is 7 years old. What?? You had no idea. Then on page 10 I mention that she wags her tail. Oh. Okay… Then I mention that she’s on a rug in the Oval Office.

This is not fun. You’ve put all this effort into meeting the story halfway, into painting the mental pictures that will make it come alive, only to be told, repeatedly, to throw away that work and start again. And is anything gained in the process?

I’m going to be mysterious and cryptic and vague, and this will make you mad with desire to read more.

No, it will not. I promise, it will not.

There’s a difference between intriguing mystery and annoying mystery.

Intriguing mystery is where I see something I don’t fully understand, but I’m assured that I’ll soon figure out what’s going on—e.g., our story opens with a man standing on a street corner in the rain, crying, holding a dictionary. I have no idea why yet, but I’m intrigued. And I know what to picture. I’m oriented.

Annoying mystery is more like our story opens with a Nanoplantus devouring a Pumperlater in the flotilla of Gorgon 6, which of course was dissolving into candles of desire because the eight ball was dead. Or it might look like Janet staring out a window, remembering the day it all happened, that fateful day when Olaf discovered the secret, and if only she’d found him before the thing happened, it might have turned out differently.

In both cases: I have no idea what to picture. My questions aren’t along the lines of Ooh, what happens next? but more What the hell is going on here? Who are these people? Why should I care? In other words, we’re intrigued—enticed into reading more—when we have enough to orient us, enough to look at, so that we’re 95% grounded and only maybe 5% lost.

How do we fix it?

Of course, the problem is that you want to get your story going quickly; you don’t want to give us the whole Wikipedia entry on your world first.

But do note that it’s actually possible to gracefully start your story or novel with the lay of the land. Consider the elegant and sure-handed opening of Richard Russo’s Empire Falls:

Compared to the Whiting mansion in town, the house Charles Beaumont Whiting built a decade after his return to Maine was modest. By every other standard of Empire Falls, where most single-family homes cost well under seventy-five thousand dollars, his was palatial, with five bedrooms, five full baths, and a detached artist's studio. C. B. Whiting had spent several formative years in old Mexico, and the house he built, appearances be damned, was a mission-style hacienda. He even had the bricks specially textured and painted tan to resemble adobe. A damn-fool house to build in central Maine, people said, though they didn't say it to him.

But quite often, a skillful writer will instead choose to fold information into action. Details of context might be inferred, or stated outright, or some combination of the two, but they feel secondary to the action (even as they’re doing a lot of heavy lifting).

Let’s look at the opening of T. C. Boyle’s novel The Women. I’ve bolded the phrases that give us contextual and orienting information.

I didn’t know much about automobiles* at the time—still don’t*, for that matter—but it was an automobile that took me* to Taliesin* in the fall of 1932*, through a country alternately fortified with trees and rolled out like a carpet to the back wall of its barns, hayricks and farmhouses*, through towns with names like Black Earth, Mazomanie and Coon Rock*, where no one in living memory had ever seen a Japanese face*.

This must be a while back; automobiles are new, and still being called “automobiles”; and our narrator is a little out of his element. (Note: I’m saying “his” because it does turn out to be a male narrator, although technically we don’t know that yet.)

“Still don’t” is doing a lot of work here; time has passed, perhaps quite a lot of time, and we’re looking back on this through the lens of retrospect.

“Me” implies that he’s alone.

Taliesin might just be a name to you, or you might know that it was Frank Lloyd Wright’s Wisconsin house and studio. You’re fine if you don’t know this, though, because we have so much other orienting information

It’s the fall of 1932! Look how you can just come right out and say it!

We can see the country here; it’s rural, it’s beautiful, it’s sparsely populated.

These towns might mean something to you, or they might just be evocative names.

Our narrator is Japanese, or of Japanese heritage, and I’m already pretty worried about him.

Now let’s look at the opening of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon. This time I’ve bolded stuff, but I’m not going to spell out what everything indicates (you’ve got it, you’re smart); but do note here that some of these details are logistics, and some are more about cultural context.

The North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance agent promised to fly from Mercy to the other side of Lake Superior at three o'clock. Two days before the event was to take place he tacked a note on the door of his little yellow house:

At 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday the 18th of February, 1931, I will take off from Mercy and fly away on my own wings. Please forgive me. I loved you all.

(signed) Robert Smith,

Ins. agent

Mr. Smith didn't draw as big a crowd as Lindbergh had four years earlier—not more than forty or fifty people showed up—because it was already eleven o'clock in the morning, on the very Wednesday he had chosen for his flight, before anybody read the note. At that time of day, during the middle of the week, word-of-mouth news just lumbered along. Children were in school; men were at work; and most of the women were fastening their corsets and getting ready to go see what tails or entrails the butcher might be giving away.

Keep going…

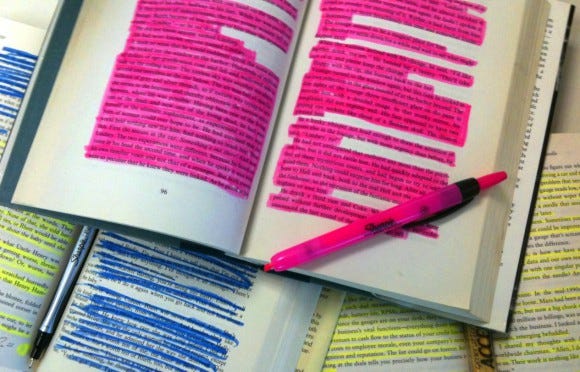

You can do this with any book on your shelf. Pull out five books right now (seriously!) and look for how the author is orienting you. Maybe even attack the pages with a highlighter, marking up every orienting phrase. If you write fantasy or sci-fi, make sure some of those books are in the mix. If you write memoir, look at memoirs.

You’ll find some authors who give you the whole lay of the land, others who fill you in on the fly, others who start with action and then zoom back to tell you about the world. But they’re all doing that work, one way or another.

Also note that most of them are filling us in on a need-to-know basis. In other words: In that Boyle passage above, he is not yet telling us about Frank Lloyd Wright (we don’t need that info yet), but he is filling us in on the Wisconsin countryside, because that’s where the action currently is. He’s not getting ahead of himself, but he’s also not leaving us behind. We tend to do the same when we tell a story socially. “…and then my uncle—well, the thing you need to know about my uncle is that he’s seven feet tall—my uncle walks into the room, and…”

(Update: I got some great questions about this post, and made a Part 2.)

Also…

A reminder that if you’re here because you’re a writer, I’m teaching a six-session online novel class this fall, one you can watch live or as recordings.

Sign up or read more here:

(Update from the future: The live class has passed, but this link will take you to the on-demand version!)

Give me a writer who employs any of those four techniques and I will show you a person who behaves passive-aggressively in real life, and who is most like to vaguebook on FB. There's an element of "testing" to the communication style - "if you really care, you will ask., or be patient enough to wait till all is explained." It's irritating. And for crying out loud, if an editor, or mentor, or trusted reader points it out, don't react defensively. JUST FIX IT. Those who won't haven't grasped the one thing I always tell my students on the first day: "All writing is rewriting." And rewriting is harder than writing. Some people just can't bear that they didn't get it right the first time, they are just awaiting validation, not constructive criticism. Some seem to believe that writing is not hard work. It's like raising children - the toughest job you'll ever love, as the old Peace Corps ad went.

I personally take great pleasure in finding ways to situate the reader with orienting details, the kind found in the literary examples you gave. In prison, I was transferred to 6 different places with very distinct personalities, and in my memoir, I had to characterize them in quick and vivid strokes, only getting very detailed about one week in a cacophonous hell-hole, where the physical layout was extremely important.

Clarity in this regard is super-important if your audience includes audiobook readers. It's annoying enough to feel lost when you're reading a book-book, but you can go back a few pages to check. If it happens in an audiobook, it's lethal.

Thank you for this, as usual.

I'm one of those magazine editors you talk about and I agree - that's a common frustration reading short stories that are submitted - the confusion about where we are, who these people are, which leads to why should I care? Or more precisely, I don't care because you've confused me. One rule for writers (and there aren't many) Don't make your reader feel dumb.