Last week (for writers and readers both), I started sharing part of my ginormous handout on endings, the one I’ve stopped printing for students because of the significant deforestation effect. If you haven’t read Part 1, start there and then join us back here for Part 2. (That would be part 2 of many… The irony of my endings handout never ending is not lost on me.)

We were talking last time about resolution or the lack thereof.

This time, we’re talking about one of the many elements that can make an ending feel like an ending: a sense of structural completion. Not every ending relies on the structure of the whole! But some of them do.

We can be super fancy and call these extrinsic endings, meaning they come not from the action of the story or from character motivation, but from the structure of the piece.

I talked last time about intrinsic endings, in which a plot point is so final that the book must be over. But with an extrinsic ending, the structure itself suggests that we must be done.

Here are some ways this is achieved…

Through Timeframe

Often, a story feels complete because we reach the end of an established timeframe or event, an ending we were waiting for structurally.

The End of an Era:

The end of the story might be the end of an era—like an education (Curtis Sittenfeld’s Prep), or a school year (each Harry Potter book), or the end of someone’s time in New York, when the book was very much about their life in New York.

The End of a Certain Timeframe:

Or the entire book or story itself might take place within the timetable of some set event—one wedding weekend, as with Maggie Shipstead’s Seating Arrangements, or the course of the ice storm in Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm. Election by Tom Perrotta takes one high school class election as its framework. Cheryl Strayed’s Wild happens during the time she spent hiking the Pacific Crest Trail.

The Ticking Clock:

There might be a ticking clock on the whole story (in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, you know he’s got to get this ghost thing resolved by Christmas morning) or the ticking clock could come along late in the game but still point precisely to where the ending will be (When Harry Met Sally, for instance, doesn’t really work if you take New Years Eve out of the end).

If you’re writing a sprawling thing that seems to lack structure and momentum, you might consider an external timeframe and the ending this might lead you to. Some of the many timeframes that work well: school years, holidays, elections, wars, parties, family reunions, trips, competitions, the course of a love affair, the course of a trial or investigation, the process of baking a cake or buying a house (I’m looking at you, HGTV—although an entire novel about baking one cake would be awesome), or even someone’s entire career or entire life, when it’s established that that’s our framework.

I do think that in a loose sense, a bildungsroman (a coming-of-age story) works this same way; we’re waiting, structurally, for the character to reach adulthood. Barbara Kingsolver’s recent (brilliant) Demon Copperhead does this beautifully (as, of course, does David Copperfield, on which it’s based).

Through Narrative Structure

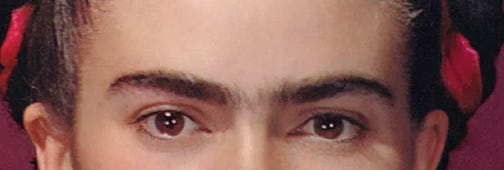

But it could also be that the narrative structure itself, separate from the timeframe of the story, promises a structural landing point. This is why when you start reading a listicle called “Seventeen Celebrity Unibrows” you’re probably going to read it all the way through; it said seventeen, and you’re going to see seventeen unibrows even if it makes you late for work, damnit!

Announced Narrative Structure:

The narrative structure might be present in the title or visually apparent:

Think of the movie Four Weddings and a Funeral: Once you’ve been through the first three weddings and the funeral, you know pretty much where you stand. There was a structural promise made in the title, one that sets our expectations, provides a road map, and lets us know when the end is near. (I actually think the movie would kind of fall apart without the title.)

Here’s Roxane Gay’s short story “Contrapasso,” which borrows the form of a dinner menu. When we get to the after-dinner drinks, we’re obviously going to be done.

Here’s Bonnie Jo Campbell’s story “The Solutions To Ben’s Problem,” which takes a list form. It’s visually clear from the outset that there are seven possible solutions, and so by the time we get to the seventh, we feel a sense of completion.

Apparent Narrative Structure:

Or there could be a narrative structure we cop to as we go.

Think of the ending of the movie Clue (or rather the VHS combined-ending version, which is what I grew up on)… “That’s how it could have happened. But how about this?” and then, later, “But here’s what really happened.” With that final announcement, we know the movie is really almost over.

Hernan Diaz’s recent novel Trust works kind of similarly. We think we’re reading one book, then we’re actually reading another, then we get the truth, then we really get the truth (or do we?)… Those four sections are right there in the table of contents, and by at least the time we reach the third section, we realize the novel is going to be four distinct things; now we’re waiting not for some huge plot point but simply for the fourth and final version of the story.

Envelope Structure:

Or we could achieve a structural sense of ending through a return to an enveloping structure.

Think of something like The Princess Bride (the movie, in this case), in which we have an outer narrative of Peter Falk talking to Fred Savage (in perhaps the greatest duo casting in history). The rest of the movie is the story Peter Falk is telling. It would be wildly unsatisfactory if the movie did not end where it had started, back on the two of them in the bedroom. And while they’ve popped in a few times throughout the film, ultimately landing back in the room with them signals to us that this story is wrapping up.

In some cases, the envelope is there only at the beginning and the end. We might even have forgotten that the outer story existed, until we return to it in the last pages. (And aren’t endings supposed to be surprising but inevitable?)

Often, the framework is of someone telling a story to someone else, with the story they tell comprising the bulk of the overall narrative. Think Ethan Frome or Wuthering Heights or Heart of Darkness.

Other times, the inner story is not told at all, but remembered—with that outer envelope being the present day, and the inner story being what’s remembered.

An example of this won’t fit here, but a typical structure (with apologies to John Knowles’s A Separate Peace) is as follows:

I went back and walked around my old boarding school. (a few pages)

I remembered this thing that happened there, when my roommate fell out of a tree and died, or maybe I caused it, and I was probably in love with him. (bulk of the book)

I walked around some more and thought about my service in the war, and made appropriate comparisons between boarding school and war. (a few pages)

I’ll add a caveat here that this structure needs to have a point. Perhaps, as in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, the listener is profoundly changed. Or maybe the envelope itself is a fascinating story.

But here’s a setup that does not work:

A guy waters a plant and stares out a window. Then he remembers this love affair he once had. Then he leaves the window and goes to bed.

I’ve read a version of this story in nearly every workshop I’ve ever taught. The problem is: Nothing changed for this guy in the present. And the story of someone looking out a window and watering a plant is not intrinsically interesting. So why on earth tell the story this way? Why put the filter of memory between us and the action?

The Callback:

A much subtler version of this return to where we started is the callback.

If you’re watching a movie and the characters return to the setting where everything started, and the music from the beginning starts playing again, you have a solid sense that thing are wrapping up.

Fiction can’t use music (alas!) but there are many other ways we can circle back.

It might indeed be the return to an earlier setting (the characters of A Midsummer Night’s Dream all return to the court at Athens), or it might be the return of a character from early on, or we might pick up a long-forgotten plot thread (that missing cat from page 5 was finally found!), or a line of dialogue might echo an earlier one. Every good comedian knows how to wrap up a set with a callback to one of the first jokes of the night.

A callback might hearken back to the very beginning. The ending of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House repeats, almost exactly, the end of the opening paragraph. (The original says “Hill House, not sane, stood by itself…” and omits the second “its”):

Hill House itself, not sane, stood against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, its walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

Or it might just recall something from earlier in the story, perhaps something often-repeated. The end of John Irving’s The Cider House Rules ends on the words Dr. Larch used to say to the boys in his orphanage every night:

To Nurse Edna, who was in love, and to Nurse Angela, who wasn’t… there was no fault to be found in the hearts of either Dr. Stone or Dr. Larch, who were—if there ever were—Princes of Maine, Kings of New England.

Or simply think of Peter Falk ending The Princess Bride by saying to his grandson, “As you wish.”

That’s all for now… Part 3 (next weekend) will be about the various ways endings might address meaning.

Meanwhile, FINE, since you asked, here’s the 17th celebrity unibrow:

So inspiring, Rebecca! Thank you!!!

Sorta thinking "Madonna in a Fur Coat" falls into the envelope structure of the narrator who discovers the past of the actual protagonist through this diary. And that ending in which a discovery in the present reframes an entire lifetime. I'm not sure if that fits here or will in Part III, but there is no example I know of as more powerful than the ending of Maupassant's "The Necklace" when (spoiler alert) Mathilde Loisel finds out she's lived in drudgery for 10 years over fake jewels that were worth "500 francs, at most!"