I was about fourteen when I asked my mom for a baby name book for Christmas. That’s maybe not the most normal request for a non-pregnant teen, but I already took myself very seriously as a writer, and this seemed like an important tool. I didn’t really end up using it much, maybe because at fourteen, all my characters were named things like “he” and “the girl,” but I continue to care deeply about my character names, and I have a hard time latching onto a character before I’ve settled on one.

Here are six ways to name your characters, only one of which might result in a lawsuit, plus several ways not to, and a common question answered.

1: Flip at Random

The obvious. Phone books, yearbooks, baby name books, et cetera. But the key here is that you’re waiting for the name that’s just slightly weird, the name that comes alive and suggests a certain kind of person.

I was flummoxed for years by a character in my second novel (the one you haven’t read) whom I’d named Steve. Really that was half the problem. Steve is a great name, but it wasn’t a name that carried a ton of weight for me. In a moment of burn-it-all-down, I decided I’d start by changing his name. I was at the library, and I started scanning the shelves for great author names. Nothing worked, but then I saw this big glass case that was labeled “Case 1,” and I decided the guy’s name would be Case. It suggested someone preppy, someone maybe kind of empty, someone who grew up in an atmosphere in which that would not be considered a strange name. Then I suddenly had his whole character and knew everything that would happen to him, including getting attacked by bees.

2: Keep Track of Great Names

Just always have a page going in your notebook or in your notes app. Years ago, I wrote down the name “Željko” out of the end credits of a Simpsons episode, and then a few years later I wrote a whole short story called “The Disappearance of Miranda Željko.” I would link to it here, but the online journal that published it since closed down, so it doesn’t exist anymore except (I hope to God) somewhere in my email attachments.

3: Freak Out Someone You Don’t Know

I’ve never done this, but somebody needs to. Go on Facebook. Click through to a friend of a friend of a friend—or, better yet, find a random person who attended a literary event within the past year, because this is way more fun if you pick a reader. Maybe someone around the same age, from around the same place, as the people you’re writing about. Now pick all the names you need off that one person’s friend list. And then imagine their absolute confusion and descent into solipsism when they find your novel and discover that literally everyone in it has the same name as a person they know.

4: Auction Off Naming Rights

This is what I did (sort of) with my latest novel. It was Amazon Prime day in the summer of 2019, and I wanted to do something to support independent bookstores instead… So I offered on Twitter that if you ordered my previous book from an indie bookstore*, and showed me the receipt, I’d name a character after you.

Here was the original tweet:

I ended up with about 20 names, and they were SUCH good names. (I should note that I only did this because it was a book about looking back on high school, and I knew I’d need a ton of very-minor-character names anyway, and they could be just about any kind of name. You really can’t do this if you’re writing a book about 18th century France and then you have to incorporate someone named Jayden Goldberg-Chow.)

Anyway, I promised that these characters would be super minor, but then a couple of times, things got out of hand and the characters grew and grew. I had to get back in touch with a couple of people (Hi, Beth Docherty!) to check if it was cool to still attach their name to a much more prominent character.

I’ve also seen people do this for charity (i.e., to support a silent auction for a literary organization, an author will auction off naming rights to a character or a restaurant or a street). You could also try to work this in reverse; tell people that if they don’t pay you money, you’ll put their full name right into your novel.

5: The Magical Baby Name Tracker

There’s this amazing linguist named Laura Wattenberg whose book The Baby Name Wizard was my bible when I was name-hunting for my own kids. She doesn’t just give you the meaning (half those meanings in baby name books are made up anyway, I swear; not every single name can mean “precious gift from God”), but actually analyzes why names get popular, which names are about the peak, what names will sound really dated in forty years.

Her original website has shut down, but she’s replicated its famous baby name tracker on her new one, Namerology.com, and while I apologize for all the time you’re about to lose messing around there, it’s SO useful. You’re able to track the popularity of any name over time, find kindred names, see discussion boards about individual names… Honestly, you might never eat or use the bathroom again.

6: Give Us Something At Least Slightly Memorable

If you’re not writing in serial like Charles Dickens, you don’t need to make every name something like Barnacle Fishblubber just so we’ll remember it when we pick up the next section three months later. But there should at least be some there there, something to hold onto. This can be a little harder for male names, or at least for males of the generation before everyone was named Sandopher or Wilder or Colt. So you might go for a last name (I’m on board with a guy everyone calls Green or Walsh or Moskowitz); or for a double name (James Avery, or John Michael), even outside of the American South; or a nickname, explained or unexplained (Chef, Peanut, Jacko, Fred-Ex); or a name from a culture distinct from most of the characters you’re writing about (Dragomir! I dare you!)…

Things not to do:

Don’t let any names be too similar. Don’t give us a Luke and a Lucas. You also don’t need a Dave and a Dan. We’re not gonna keep track of that shit. You might not even want a June and a Rose. Yes, they start with different letters, but they telegraph the same generation, the same feel, the same allusion to nature…

You’re not Nathaniel Hawthorne, and you’re not writing to please your tenth-grade English teacher—so you don’t need your names to mean things, unless you want to suggest that the character’s parents chose the name for the meaning. We don’t need Goodman Merriwether, and we don’t need Loki Damon, and we don’t need Barbie Vandervander (which doesn’t actually mean what it sounds like, but we all know what you’re getting at).

Don’t steal a name from a random book spine without first Googling the person. I found the name Jake Austen on a book and used it in The Great Believers because… I mean, it’s a great name. Then after publication I learned that I know the guy’s brother, which was a little awkward.

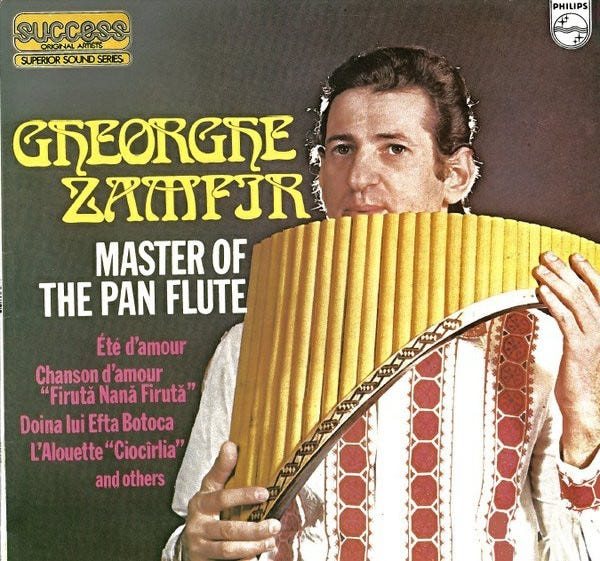

Honestly, don’t use any name without Googling it first. In the original draft of a short story, I named a Romanian musician “Zamfir”; my husband fortunately cracked up and explained that anyone even slightly older than me would instantly think of this guy:

I very much dodged the pan flute bullet there.

Don’t use names from a culture you don’t know well without running the names by someone who does know that culture well. If you name two brothers Paco and Francisco, people who know Spanish are going to laugh at you, or at least be deeply confused. Your helpful friend can also keep you from naming a character something bizarrely old-fashioned, or can get you beyond the most obvious choices. (In my experience, fully 90% of Hungarian men in English-language books are unnecessarily named László, maybe because it’s easy to pronounce.)

A Question:

Do I have to get permission from someone before using their name in a book?

Well… It depends on whether a) you know the person, and b) you’re writing fiction or nonfiction, and c) whether they’re famous.

Keeping in mind that I’m not a lawyer:

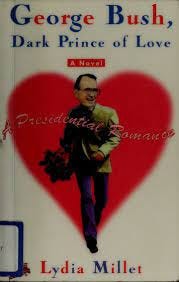

If they’re famous, they’re fair game for fiction or nonfiction. Behold this novel that Lydia Millet once wrote:

If you happen to use the name of a non-famous person you don’t know, you’re also absolutely fine. Otherwise, any time someone named a character Sarah Johnson, they could get sued by anyone on the planet named Sarah Johnson. Fortunately, that’s not. the case.

If you know the person and give other true, identifying characteristics (their place of work, their address) and especially if it’s an unflattering portrayal, you’d probably better check with your lawyer first.

Similarly, if you’re writing memoir and giving real names of non-famous people, your lawyer or your press’s lawyer will likely want to get clearance first.

But say there’s a name you’re obsessed with. For instance: I keep passing a storefront for an interior decorator named Soledad Zitzewitz. I cannot get this name out of my head. It’s amazing. If I used it, I wouldn’t want to make her an interior decorator from outside Chicago. But I could make her a doctor from Florida, especially since I’ve never met her.

*What was that footnote about?

Speaking of indie bookstores…

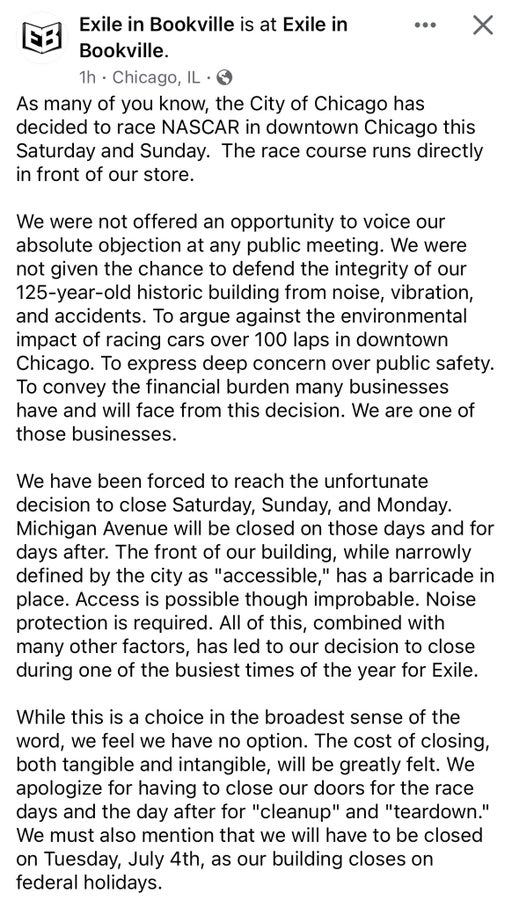

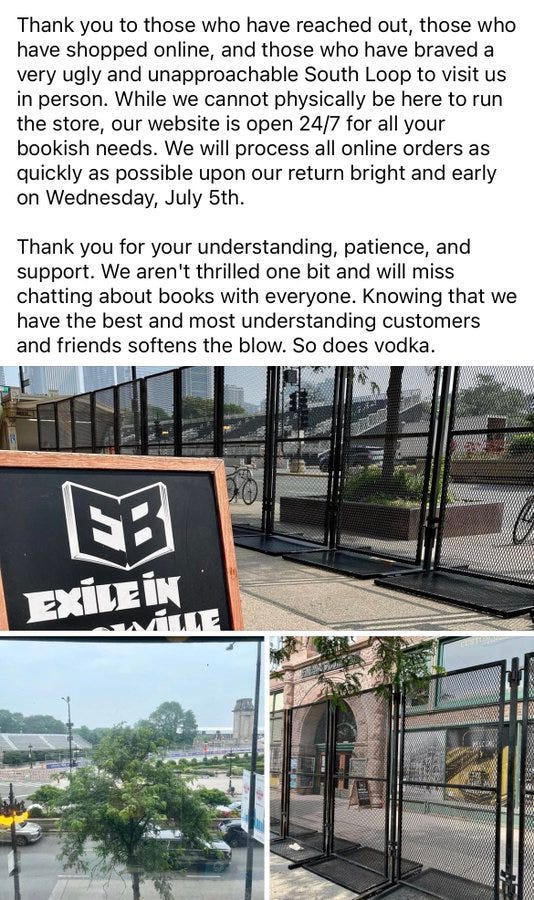

Chicago’s absolutely wonderful Exile in Bookville is suffering this weekend because the city has been sold to Nascar and no one can enter their building. They’re losing one of their busiest weekends of sales…

Online orders are open, though, and you really should treat yourself to something wonderful, in my opinion.

A month or two ago, I was watching a TV documentary about a small town that had been through hard times. They interviewed a real person named Cat Monster. I don't remember anything else about the documentary except her name. So if I end up with a character named Gerbil Demon in some future book, you'll know why.

😂😂😂 As someone who hates naming characters and I constantly on baby name websites, I appreciated this greatly.