The Best Albanian Novel I've Ever Read!

(Okay, the only Albanian Novel I've Ever Read)

As you’ll know if you read my last post, I’m circling the world by reading 84 books in translation. After jaunts through Hungary, Croatia, Bosnia, and Austria, I’ve landed in Albania with The File on H., a comic (sort of) 1981 novel by Ismail Kadare, translated by… well, we’ll get to the translation in a second.

You do NOT HAVE TO HAVE KNOW THIS BOOK to read on and learn some stuff about this guy before he wins the Nobel, and also to hear the world’s worst riddle.

First, an inadequate attempt to describe this novel:

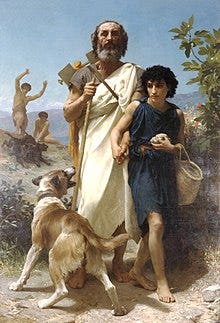

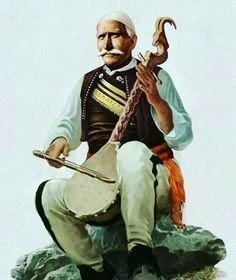

Two Homeric scholars from Ireland-via-Harvard travel to rural Albania to record the rhapsodes (minstrels) who still perform Albanian epic poetry, hoping therein to find some insight into Homer himself. (He’s the “H.”)

But!

The local governor is convinced that the two men are spies, and sends someone to spy on them in turn. The governor’s wife is determined to sleep with one of the scholars. There’s a hermit who’s mad at them. And everyone is incredibly freaked out by the enormous voice recorder they’ve lugged with them, and worried about the way it’s trapping voices inside.

The narration itself is fascinating: Much of it paraphrases the reports of the Albanian spy, Dull, while also giving us things Dull couldn’t be there for (the scholars’ thoughts, the governor’s reaction on reading Dull’s reports)… but at the same time, the governor is described as being SO impressed with Dull’s brilliant reporting, that we (or at least I) get the sense the the whole entire thing is being written up later by Dull… or at least by some Dull-like narrative force spying on absolutely everyone.

We’ll stay spoiler-free, but the ending is a perfect solution to the problem of the book, at once a tragic blow and a final triumph.

Takeaways and quotes:

God, I love me some good narrative fuckery. The idea of an omniscient narrator is ridiculous to begin with, so why not have fun with it? Why not call the entire machinery of narration into question?

I’m alarmed at how little thought I’ve given Homer. I knew that he was maybe one guy or maybe many, and that he might have been blind. I imagined him sort of rolling into town and gathering people around a fire and holding forth. I looked him up today and learned he was the son of the river Meles and the nymph Critheïs (uh, sure!) and that he died after failing to solve a fisherman’s riddle. (I so hope this is true. More on that below.) But in my mind he existed in isolation, not as part of an ongoing tradition. And the book, despite being a novel, really digs into this tradition in the way nonfiction would.

The book in a nutshell: “… Bill and Max felt that they had succeeded in weaving the Albanian epic onto the reels of their tape-recording machine. Each morning when they woke, their eyes turned automatically toward its quietly gleaming lid. They liked to remind themselves that the creation of that device was like a miracle. It seemed to have been decreed that the solution of the Homeric enigma had had to wait until tape recorders had been invented.”

This is much more a book about how people see each other than about who they actually are. And the literal act of seeing is thematically central… One of the scholars is going blind, like Homer. The governor’s wife falls in love with the scholars before she’s seen them. No one has ever seen Dull in person; and Dull’s great legendary strength is his ears.

Of the five books I’ve read so far in this adventure, this one taught me the most about where it’s set.

I said I’d talk about the translation… I love this. It appeared in Albanian in 1981, and was then translated into French in 1989, and revised in 1996 (no idea why) by Jusuf Vrioni. The English translator, David Bellos, is actually a French scholar. He translated from the French, and published the book in English in 1997. Normally I’d have questions about a translation of a translation, but it seems so delightful apt to the themes of the book.

A sidebar:

When my younger daughter was 9, some translations of my last novel showed up at the house (German, I think) with the word “roman” on the bottom, as in the photo above, and she asked why every time they translated my novel, they translated it into Roman.

The Author:

Kadare is still alive (86) and living in Paris, where—after decades of couching his political criticisms in metaphor—he moved in 1990 to write freely.

If I weren’t continuing my travels, I’d stop in Albania and read The General of the Dead Army, his first and most famous novel. I’d love to hear from any of you who’ve read it!

So, an almost-87-year-old dissident Albanian writer with an important list, who’s been nominated fifteen times for the Nobel… and the only Albanian Nobel winner so far has been Mother Teresa… I’m too lazy to place bets, but one of you should.

Hold up, what riddle killed Homer??

Yeah, it’s really stupid.

The story is that three young fishing boys stopped him and gave him this riddle:

“Those we caught we left behind; those we did not catch, we bring.”

He could not solve it, and was so upset with himself that he turned and slipped in the mud and died.

The answer, wait for it, wait for it, is… lice.

Hilarious! Totally worth dying for.

But also… Who told that story later? The three boys aren’t gonna go bragging in town that they killed this poor old poet. Homer’s not alive to tell about it. So our informant must be a spy.

What’s next?

THIS sucker. The Murderess, by Alexandros Papadiamantis. It’s short and Greek…

On Friday, I’ll send out the next six on the list—from Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Yemen, and Egypt.

If you have favorite books in translation from anywhere, I want to hear about them! The list is still under construction. And if you’ve read any Kadare, please tell all.

We are also open to riddles about parasites.

I legitimately laughed out loud throughout reading this book and read parts to my husband. I, too, was fascinated by the translation from the French and how it managed to stay funny. I suspect if I could read the Albanian it would be howlingly funny.

The reverence and fear for the tape recorder: priceless. The wife's journey--brilliant. And planted so perfectly in the opening pages. By the end of the book, I was a little in love with both scholars.

I've never read anything like this book; I'm not typically drawn to farcical novels but maybe I've been wrong not to be?

This is an amazing description of this novel, Rebecca! Whoa! You yourself are 100% amazing, to be diving into all this reading in translation with such panache and thought. I do have one novel to suggest -- THE SAFE HOUSE, by Christophe Boltanski, translated by a wonderful young translator, Laura Marris. (She's also recently translated The Plague with great beauty.) The Safe House is (according to the University of Chicago description) an "ingeniously structured, lightly fictionalized account of [Boltanski's Jewish] grandparents and their extended family [during World War II, in Paris]. The novel unfolds room by room—each chapter opening with a floorplan— introducing us to the characters who occupy each room, including the narrator’s grandmother--a woman of “savage appetites”--and his uncle Christian, whose haunted artworks would one day make him famous." I'm sure you already have more suggestions than you need! but if not, this one is great!