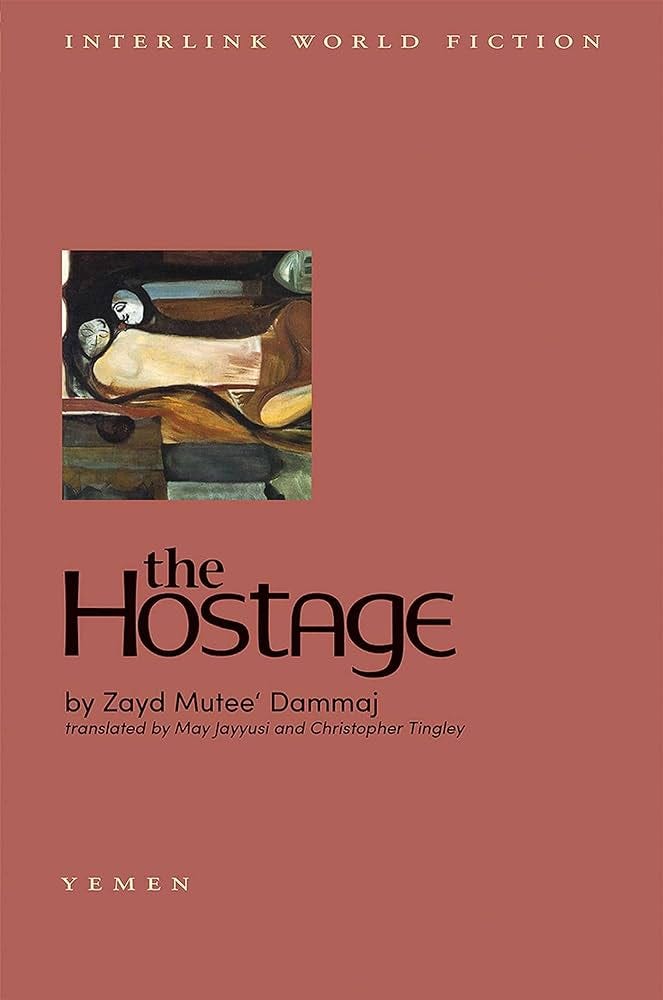

As most of you know, I’ve been reading my way around the world (here’s why)… and although it took me a hot second, I’ve finally finished my eleventh book, the short novel The Hostage by the Yemeni author Zayd Mutee’ Damaj, translated by May Jayyusi and Christopher Tingley. Before I lose you: This book is not nearly as dark or disturbing as the title would suggest. It’s often lighthearted and sometimes very funny, and in many ways it’s a twisted love story.

Before we go any further, I have to get this out of my system:

Okay, apologies, moving on.

This is a slender book (128 pages), and an easy read. Most of you would likely read it in one or two sittings. The reason it took me so long (two months, yikes) is that I left the book in a hotel room and had to order a new copy, and it took a long time to arrive. Or at least I thought I’d left it in the hotel. A few days after the new one arrived, I found the old one in an obscure backpack pocket. (A hazard of slim books, I guess.) So now I have two of these.

I want to mention first that this is the most impressed I’ve been, so far, with the publisher’s presentation of a translated work. First of all, Interlink World Fiction has put the translators’ names on the cover—something becoming more common these days, but still too rare. And then there’s both a preface about the context and importance of the book and a historical introduction that manages to explain Yemen in a way that perfectly frames the book but also helped me understand the background to the ongoing civil war there better than any news article I’ve read. (Did you know that the US is currently launching airstrikes at Yemen? It doesn’t feel like that’s getting a lot of media attention.)

Published in 1984, the novel is set in 1948. A nameless first-person protagonist, a young teenage boy, is taken hostage to ensure his father’s loyalty to the Imam. As the historical note explains, this was a common practice—and Dammaj himself apparently once visited a cousin who was being held at the same castle where the narrator is originally taken.

The hostage is transferred to the governor’s palace to become a “duwaydar,” a well-treated servant whose most onerous task is rubbing the governor’s feet. His roommate, the slightly older “handsome duwaydar,” services many of the palace’s women in various late-night visits. How voluntary these duties are is never fully spelled out, perhaps because what’s voluntary, and how much freedom or power the two duwaydars have, is always in question and in flux. (The modern reader will of course come down on the side of these relationships being entirely nonconsensual, but that does not seem the clear intention of the book. The narrator, at least, does not dwell on this aspect as particularly alarming.)

The protagonist’s duties include sending messages between Sharifa Hafsa—the governor’s beautiful sister—and a fatuous poet in the court of the Imam. The hostage and the Sharifa are mutually infatuated, although when one party has the option to shackle the other, the relationship is fairly doomed. I love a novel that asks more questions than it answers, and this one asks disturbingly complicated questions about servitude and free will. I feel like if I spent a week writing a graduate-level paper, I could figure out some of what it’s saying there, but since I’m not in grad school anymore I’m content to just let the story unsettle me.

I noted recently that I was encountering a lot of translated novels that were much more reliant on summary and exposition than on scene. This one bucked the trend, and felt more familiar and comfortable to me in its framing and pacing—but also had a confident hand with the passage of time, letting long periods elapse very quickly.

Both the author and his father were politicians; his father was a revolutionary against the Imam Yahya, and became a governor after the 1962 revolution, while the author himself served in parliament, as a governor, and as the ambassador to Kuwait. (He died at the age of 57 in 2000.) Meanwhile his son, Hamdan Dammag, is apparently a computer scientist and a novelist and an editor and works in human rights. I mean, I did make a salad yesterday in addition to thinking about writing, so same-same.

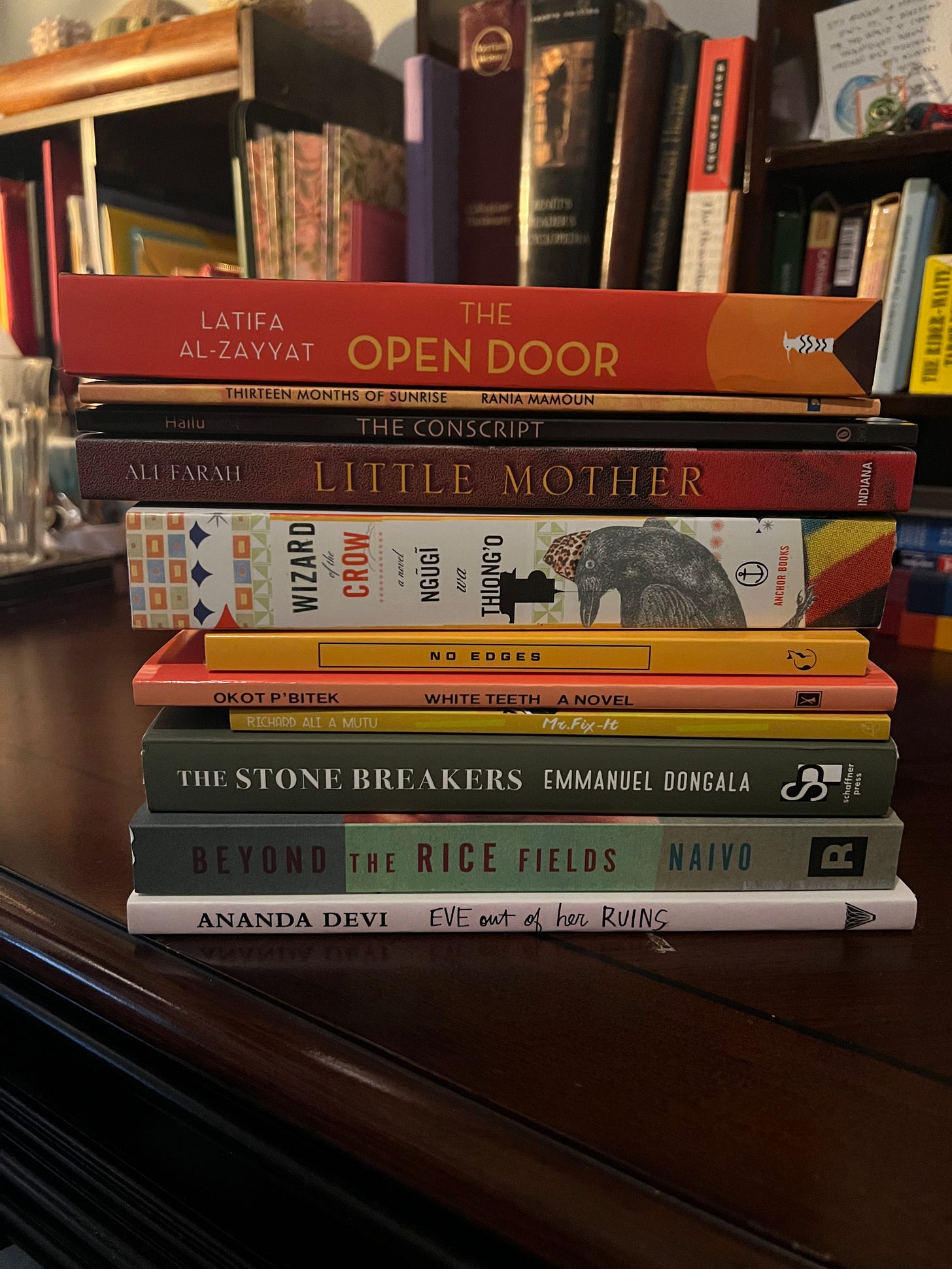

I’m leaving Asia behind for a minute (well, probably almost a year) and… I’m very excited about this… starting in on some African books. The African fiction I’ve read has been primarily from Nigeria and South Africa, and almost all of it was originally written in English. I’m going to fix that.

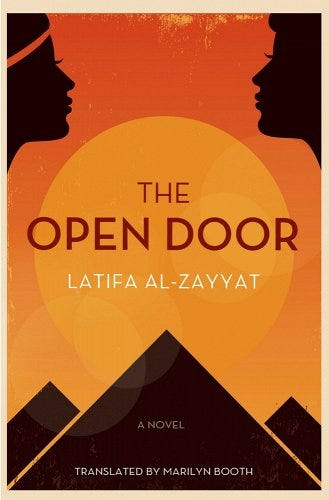

My first book (and I really hope some of you will read along with me) is from Egypt: The Open Door by Latifa Al-Zayyat, translated from the Arabic by Marilyn Booth, published by Hoopoe. This one is from 1960, and was written in colloquial Egyptian Arabic, unusual for the time. It’s about a girl’s political and sexual coming-of-age in the 1940s and ‘50s; the critic Ferial Ghazoul has called it “a great anticolonialist work in a feminist key.”

I tried wherever possible to find novels translated from African languages rather than the languages of colonizers, but this is sometimes an unfortunately a tall order. Not only would the book need to have achieved its original publication (in some regions, difficult for books not written in English or French) but it would then need to have found translation and publication in English. To give you a sense of it: The Swahili story collection I’ve chosen, published in 2023 by Two Lines Press, is the first collection of Swahili stories in English translation. The first. And that’s Swahili, a major language spoken in several countries. Out of eleven books, I found seven from indigenous languages (I’m counting Arabic for Egypt and Sudan here) and four from French and Italian.

Here’s the area I’m covering this time, although of course national boundaries are not always relevant. Green is what I've already read, and purple is what I’ve planned.

When I circle back around the world (it’ll be a year or two) I’ll get to Africa again and hit some of the western parts.

And (drum roll) here are all the books:

Sudan: Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette

Eritrea: The Conscript by Gebreyesus Hallu, translated from the Tigrinya by Ghirmai Negash

Somalia: Little Mother by Cristina Ali Farah, translated from the Italian by Alessandra di Maio

Kenya: Wizard of the Crow, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, translated from the Gīkūyū by the author

Tanzania/Kenya: No Edges: Swahili Stories (a story anthology), translated from the Swahili by several translators

Uganda: White Teeth by Okot p’Bitek, translated from the Acoli by the author

Democratic Republic of Congo: Mr. Fix-It by Richard Ali A Matu, translated from the Lingala by Bienvenu and Sara Sene

Republic of the Congo: The Stone Breakers by Emmanuel Dongala, translated from the French by Sarah Hanaburgh

Madagascar: Beyond the Rice Fields by Naivo, translated from the French by Allison M. Charette

Mauritius: Eve Out of Her Ruins by Ananda Devi, translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman

I’m aiming to get through all of them in 2024, although we’ll see how many I end up misplacing around the country. Join me, please! Especially if you haven’t explored very much of Africa in your reading.

I still think this is one of the best reading (group? list?) ideas I have ever encountered. If I can’t discover a place by going there physically to explore, food, literature, and language are the next best.

2023 was too floppy for me, so maybe I will be going to Africa in 2024.

At the National Book Awards this year, both the author and the translator of one of the winning books came to the stage and received an award. It's nice to see that they're getting more recognition.