For both readers and writers, I’ve been sharing part of my ginormous handout on endings, piece by piece. Here are Part 1, and Part 2, and Part 3 (although you really don’t have to read them in order).

Today we’re talking about the way sound works at the end of a piece of prose. When I end something, I switch from thinking like a fiction writer to thinking like a poet. I’m often quite literally tapping out the rhythm of those final sentences on my desk. Of course lyricism matters all the way through a piece, but there’s something about those last words, the echo you’re going to leave in everyone’s ears, that matters more.

I’m incredibly jealous of the way a TV show might wrap things up with music… We don’t have that ability on the page, but fortunately we have some other tricks.

So here are some ways that endings might emphasize sound.

Lyricism

Well, all endings should all be lyrical, to an extent. In the last lines, more than anywhere else in your story, you need to listen for sound. You should think about the consonants and the vowels and the rhythm. A difference in rhythm can make one ending haunting and another just thud. But some writers can get away with going way over the top on the lyricism.

For instance, here’s the ending of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man; it even rhymes, out of nowhere. (Listen for the “oo” sounds…)

“Ah!” I can hear you say, “so it was all a buildup to bore us with his buggy jiving! He only wanted us to listen to him rave!” But only partly true. Being invisible and without substance, a disembodied voice, as it were, what else could I do? What else but try to tell you what was really happening when your eyes were looking through!

And it is this which frightens me:

Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?

Dialogue:

Leaving us with the sound of someone talking can be remarkably effective. (And it somehow feels more auditory than plain narration.) But what is said needs to be delicately profound.

The following is from “Emergency,” by Denis Johnson. The narrator (known just as “Fuckhead”) and his friend Georgie are both orderlies in a hospital, and both of them are on heavy drugs, especially Georgie. Some messed-up stuff involving baby rabbits has just happened.

Some hours before that, Georgie had said something that had suddenly and completely explained the difference between us. We’d been driving back toward town, along the Old Highway, through the flatness. We picked up a hitchhiker, a boy I knew. We stopped the truck and the boy climbed slowly up out of the fields as out of the mouth of a volcano. His name was Hardee. He looked even worse than we probably did.

[For two pages, they drive around and Hardee tells them he’s been drafted to Vietnam and plans to get to Canada.]

After a while Hardee asked Georgie, “What do you do for a job,” and Georgie said, “I save lives.”

Other examples: Wallace Stegner’s Crossing to Safety; Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People”; Nick Flynn’s Another Bullshit Night in Suck City

Repetition:

This might be repetition, right at the end of the piece, of a word or phrase…

From William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!:

I don’t hate it he thought, panting in the cold air, the iron New England dark; I don’t. I don’t! I don’t hate it! I don’t hate it!

Other examples: Joyce’s Ulysses; Beckett’s The Unnameable

Or it might be an echo of something earlier in the book…

In Part 2, as we talked about structure, I gave a few examples of this (The Cider House Rules and The Haunting of Hill House)… Here’s one more, from Tobias Wolff’s story “Bullet in the Brain,” in which a dying literary critic recalls the words he heard during a childhood pickup baseball game that first “roused” and “elated” his love of language, words we’ve learned about earlier in the story.

(Note that he’s also using repetition, and also using quotation.)

But for now Anders can still make time. Time for the shadows to lengthen on the grass, time for the tethered dog to bark at the flying ball, time for the boy in right field to smack his sweat-blackened mitt and softly chant, They is, they is, they is.

Note: I personally loathe—loathe!—pieces that end with the words of the title, as Thomas Pynchon does in The Crying of Lot 49. But then he’s Thomas Pynchon and I’m not…

Allusion or Quotation:

Here, the author is ending on words not her own—perhaps in order to achieve resonance or historical depth.

From Alice Munro’s “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage,” in which a girl has been doing her Latin translation homework at the table when her mother tells her some shocking news:

Ignoring her mother, she wrote, “You must not ask, it is forbidden for us to know—”

She paused, chewing her pencil, then finished off with a chill of satisfaction, “—what fate has in store for me, or for you—”

Other examples: Mad Men ending on “I’d like to buy the world a Coke”

Question:

It might be sincere or philosophical or ironic or sarcastic or rhetorical… But it rings in our ears and it demands an answer.

From Jess Walter’s Beautiful Ruins:

And even if they don’t find what they’re looking for, isn’t it enough to be out walking together in the sunlight?

From Lorrie Moore’s “People Like That are the Only People Here,” in which someone has suggested that the narrator, an author, might turn her notes about her son’s cancer into a story:

These are the notes.

Now where is the money?

Other examples: Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises; Dr. Seuss, The Cat in the Hat

Apostrophe / Direct Address:

The narrator or narrative voice is suddenly speaking directly to a character (or the reader, or a country, or a thing, or a time, etc.).

From Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield:

Oh Agnes, Oh my soul, so may thy face be by me when I close my life indeed! so may I, when realities are melting from me like shadows which I now dismiss, still find thee near me, pointing upward!

Other examples: John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars

Ritardando:

Often, you can really feel the rhythm slow in the very last lines of a story, whether because of sentence length or rhythm or line breaks.

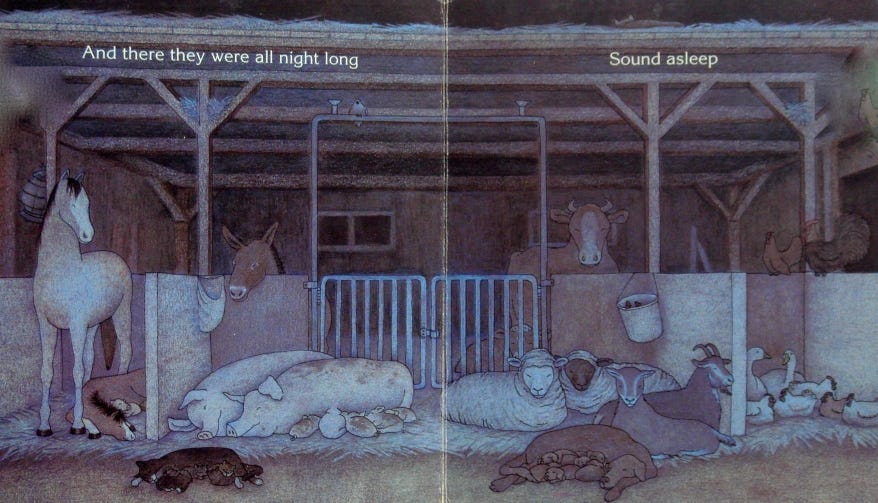

Children’s books often do this, perhaps because they’re literally trying to lull the kids to sleep. Compare these two spreads from Margaret Wise Brown’s The Big Red Barn, one from early in the book and one from (almost) the end:

(I can’t find the very last pages online, but if my memory of reading it 7,000 times to my children serves, the last pages go: In the big red barn / While the moon sailed high / In the dark night sky — one line per page, no more.)

I have saved more than one of my own endings simply by going in and pressing “return” a few times to make more paragraph breaks and slow the rhythm.

Here’s the ending of Nicole Krauss’s The History of Love:

Really, there isn’t much to say.

He was a great writer.

He fell in love.

It was his life.

Imagine if she’d stuck this all together in one chunk. It would have raced by way too fast.

That’s all for now…

Next time, we’re getting into some of my favorite stuff: endings that shift the scope, focus, or point of view.

Meanwhile, if you have favorite lyrical endings, please paste them in the comments!

"The knocking continues. The whole world seems very still. For some reason I find myself remembering a moth pupa stirring in the warmth of a train compartment somewhere between the unforgotten past and the unforeseeable future. Someone is calling my name. Since I appear to be alone in this pleasant and suddenly quite useless villa, I believe I must go and see who it is."

Paul Russell, The Unreal Life of Sergey Nabokov

Oh God, that Denis Johnson story with the smooshed bunnies...even just thinking of it makes me cover my face with my hands.

From The Post-Birthday World, by Lionel Shriver:

"Well. Did you make the right choice?"

"Yes," she determined, with a little frown. "I think so."