More Cake, More Interiority!

(Interiority, Part 3: Examples from Edward P. Jones and Alice Munro)

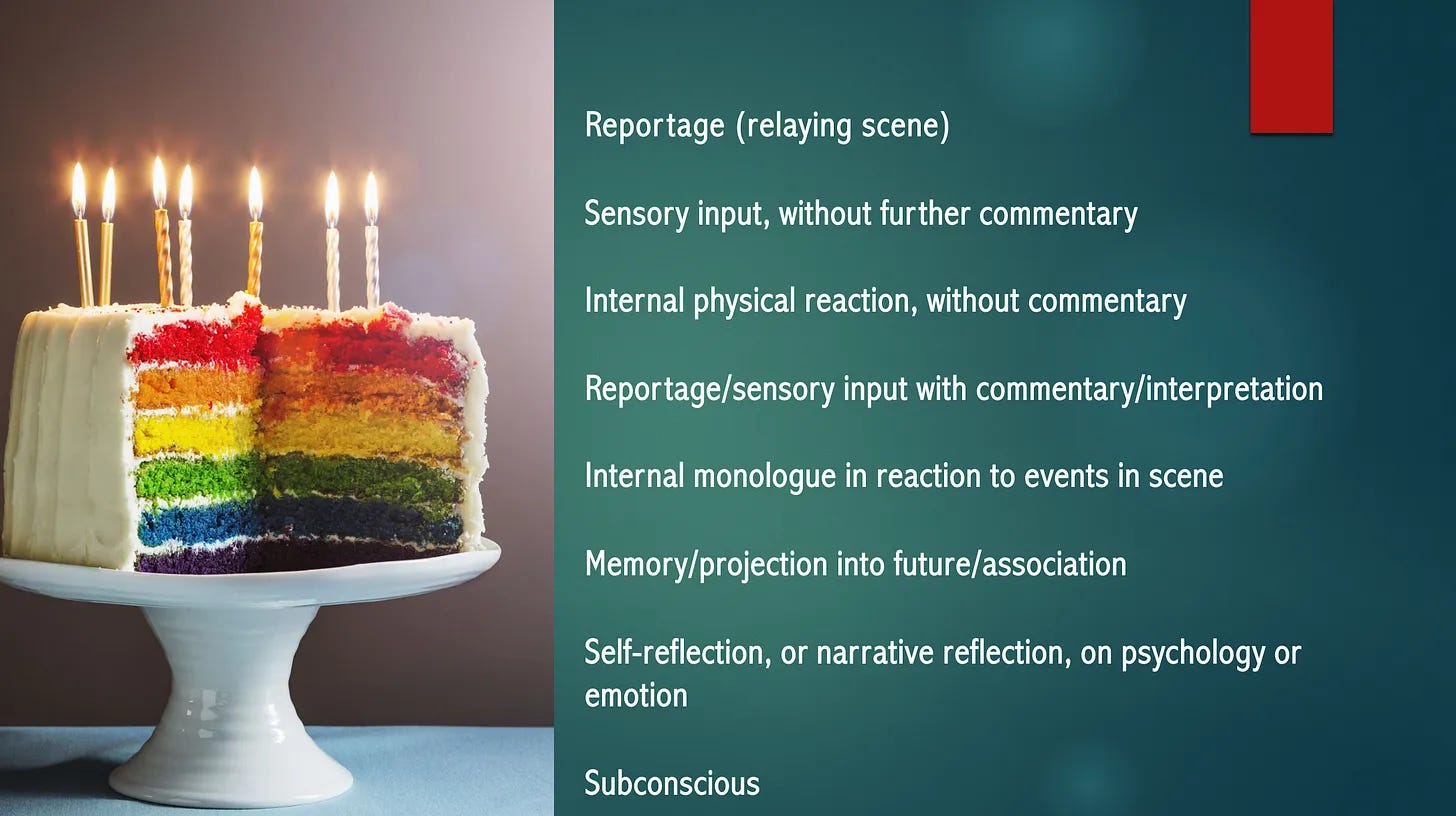

This is part three of a series on interiority (the stuff that goes on inside a character’s head). In part two, we talked about the layers of perception and reflection, from surface observations down to the subconscious—and I promised that I’d give you some good examples soon. Here they are.

I’ve been comparing the layers of interiority to layer cake, so here’s a picture of Dobos torta, a Hungarian cake that is very good but probably takes a year of your life to make at home.

Okay, moving on.

I’m going to run through two very different examples here (one from Edward P. Jones and one from Alice Munro), to answer the two most common questions I hear about interiority: 1) How do you weave interiority into action without sounding awkward? and 2) What if you have a character who’s repressed/dim/not very reflective? And just for fun, both of these examples are from stories that start in train stations. Why not.

As a quick reminder, here are the layers we were talking about:

How do I weave this stuff in?

There are writers who come at us with giant chunks of interiority (think Proust) and ones who weave it in like a fine thread. If you pulled ten books off your shelf you’d find ten different ratios of action to interiority—but here’s an example of someone doing it really subtly.

This is from the story “An Orange Line Train to Ballston,” which you can find in Edward P. Jones’s 1992 collection Lost in the City. It’s not the very beginning of the story, but close to it. A mother is waiting for the subway with her three children.

(Before I point it out, try to look for what is happening inside someone’s head versus outside.)

“How do the lights know when the train is comin?” he asked his mother.

This was a new question. “I don’t know,” she said. “Avis, stop kicking like that.” The girl continued to kick out at something imaginary in front of her and Marvella tugged at her arm until the girl stopped.

Most of what we have here is reportage—what Marvella, our point-of-view character sees and notices and does—but with “this was a new question” we also have what she’s thinking. In fact, those five questions sound very much like her internal monologue. But then we’re right back into the action.

A few sentences later, after Marvella has explained the lights:

Marvin seemed satisfied with the answer. He studied the lights and as he did they began to blink. The boy was nine. My son the engineer, his mother thought.

The word “seemed” situates us fully in Marvella’s head. (If Jones wrote “Marvin was satisfied with the answer,” but then didn’t go into Marvin’s point of view, this would be the kind of POV slip-up I discussed in Part 1. Edward P. Jones would NEVER. Then we get some reportage (“he studied the lights”) and then we get this lovely, straightforward, workmanlike exposition: “The boy was nine.” Isn’t it amazing how you can just do that? You can just come out and TELL us stuff. You really can! Even when we’re in the point of view of someone who wouldn’t really be thinking that stuff in the moment. And then, in the final sentence, we get tagged thought (something I warned against in excess in Part 1, but that works beautifully in small, subtle doses). And notice how he does it without quotes or italics, both of which would be distracting.

Then we’re back into the action again:

On the other side of Avis stood Marcus, her second son. Marvella noted out of the corner of her eye that he was yapping away, as usual, and at first Marvella thought he was talking to Avis or having another conversation with himself. “Everybody else is borin,” he said to her the first time she asked why he talked to himself. He was now seven. Long before the train came into view, it sent ahead a roar, which always made Marvella look left and right to make certain her children were safe and close. And when she turned away from the coming train, she saw that Marcus had been talking to the man with the dreadlocks.

I mean, don’t you want to read the rest of this story now??

Notice here how we don’t lose the setting or the action (in fact, the action moves very quickly, with a train bearing down and stranger danger) but we do get these moments of interiority. We hear first what Marvella “noted” and “thought”—her literal (tagged) impressions of the moment—and we also get memory and association. We’re hearing what’s “usual,” and what she “always” does to check for the trains, plus this very brief memory (look how short!) of when Marcus was younger.

I’m also fascinated by the way Jones situates us so fully in her vision and hearing (“the corner of her eye,” “yapping,” “into view,” “a roar,” “look left and right,”) that it feels like we’re turning right with her to see, suddenly, this startling thing.

What about a non-introspective character?

What if your character is deeply un-self-aware, or unwilling to share their thoughts? And that’s kind of the point? You don’t just want a void there on the page, because surely your character is thinking something. (I talked in Part 1 about Empty Head Syndrome, and it’s not a great thing.)

Here’s the beginning of Alice Munro’s short story “Amundsen,” which you can read in its entirety right here in the New Yorker. In fact, later today you really should, because near the end of the story there’s a STUNNING moment in which the narrator doesn’t allow herself to process something directly but we still know what she’s thinking, and I refuse to spoil it here.

This is how the story starts:

On the bench outside the station, I sat and waited. The station had been open when the train arrived, but now it was locked. Another woman sat at the end of the bench, holding between her knees a string bag full of parcels wrapped in oiled paper. Meat—raw meat. I could smell it.

Across the tracks was the electric train, empty, waiting.

Here we mostly have reportage. We get what she’s doing (sitting and waiting) where she is/what’s happening, what she can see and what she can smell. She does not, thank God, take us through all five senses like someone completing a fifth grade creative writing assignment—but the visuals and the smell are plenty and suggest, furthermore, both the sound of the place (quiet) and the feel of it (cold).

These are short, sparse sentences. In their simplicity, they feel repressed—quite intentionally. This is not a narrator who’s going to invite us in and make herself vulnerable to us.

No other passengers showed up, and after a while the stationmaster stuck his head out the station window and called, “San.” At first I thought he was calling a man’s name, Sam.

Here we’re getting just a tiny bit deeper into interiority because we’re getting some analysis of her own impressions: She got it wrong, then she figured it out.

And another man wearing some kind of official outfit did come around the end of the building. He crossed the tracks and boarded the electric car. The woman with the parcels stood up and followed him, so I did the same.

This is a tiny, subtle shift, but in the word “so” we’re now getting into reasoning—an explanation of why the narrator does what she does.

There was a burst of shouting from across the street, and the doors of a dark-shingled flat-roofed building opened, letting loose several men, who were jamming caps on their heads and banging lunch buckets against their thighs. By the noise they were making, you’d have thought the car was going to run away from them at any minute. But when they settled on board nothing happened.

Since we were just talking about sound: Notice how the silence (which she hasn’t even needed to mention) is shattered here by all this noise.

”You’d have thought” is an interesting move. We’re getting into that layer of projection into the future (imagining what might happen next) but the “you” simultaneously holds us at a distance (she’s not making this deeply about her) and implicates us.

The car sat while they counted one another and worked out who was missing and told the driver that he couldn’t go yet. Then somebody remembered that the missing man hadn’t been around all day. The car started, though I couldn’t tell if the driver had been listening to any of this, or cared.

More reportage here, but also the narrator is wondering about things beyond the obvious.

The men got off at a sawmill in the bush—it wouldn’t have been more than ten minutes’ walk—and shortly after that the lake came into view, covered with snow.

And here, again (with “it wouldn’t have been more than ten minutes”) a subtle sense that the narrator is thinking about things beyond the immediate present.

A long, white, wooden building in front of it. The woman readjusted her packages and stood up, and I followed. The driver again called “San,” and the doors opened. A couple of women were waiting to get on. They greeted the woman with the meat, and she said that it was a raw day.

All avoided looking at me as I climbed down behind the meat woman.

The doors banged together, and the train started back.

We’re back to simple reportage now, and it works. And again, its sparseness, it suggests a repression of emotion. This particular part reads a lot like Hemingway.

Then there was silence, the air like ice. Brittle-looking birch trees with black marks on their white bark, and some small, untidy evergreens, rolled up like sleepy bears. The frozen lake not level but mounded along the shore, as if the waves had turned to ice in the act of falling. And the building, with its deliberate rows of windows and its glassed-in porches at either end. Everything austere and northerly, black-and-white under the high dome of clouds. So still, so immense an enchantment.

While this is really just description of place, notice how many metaphors we have (air like ice, sleepy bears), plus conjecture (“as if the waves had turned to ice in the act of falling”), plus judgment calls (“brittle-looking,” “austere and northerly,” “so immense an enchantment”).

But the birch bark not white after all, as you got closer. Grayish yellow, grayish blue, gray.

Again with the “you.” She’s simultaneously giving us her impressions and drawing us in and erasing herself.

“Where you heading?” the meat woman called to me. “Visiting hours are over at three.”

“I’m not a visitor,” I said. “I’m the new teacher.”

“Well, they won’t let you in the front door, anyway,” the woman said with some satisfaction. “You better come along with me. Don’t you have a suitcase?”

“The stationmaster said he’d bring it later.”

“The way you were just standing there—looked like you were lost.”

I said that I had stopped because it was so beautiful.

“Some might think so. ’Less they were too sick or too busy.”

And here, the interiority falls away. The dialogue plows on, and we don’t need to stop after every line for emotional interpretation.

Also interesting to note where and how she breaks up the dialogue with paraphrasing (“I said that I had stopped…”). An obvious (and often helpful) move would be to paraphrase the small talk and put only the most interesting and personal line as direct dialogue. Munro has essentially done the opposite—which manages to draw special attention to that line, but also feels like a protective move from the narrator (as we aren’t allowed to hear the most personal dialogue directly). Munro is a master at breaking narrative “rules” to great effect. It’s not even fair, how good she is.

Nothing more was said until we entered the kitchen, at the far end of the building. I did not get a chance to look around me, because attention was drawn to my boots.

“You better get those off before they track the floor.”

I wrestled off the boots—there was no chair to sit down on—and set them on the mat where the woman had put hers.

Twice here we get (indirectly phrased) things the narrator wants to do, but can’t. She can’t look around, and she can’t sit down on a chair. So we’re going beyond reportage, into what isn’t: what she imagines, what she’s looking for. And of course, not being able to do what she wants sets the tone in many ways for the rest of the story.

“Pick them up and bring them with you. I don’t know where they’ll be putting you. You better keep your coat on, too. There’s no heating in the cloakroom.”

No heat, no light, except what came through a little window I could not reach. It was like being punished at school. Sent to the cloakroom. Yes. The same smell of winter clothing that never really dried out, of boots soaked through to dirty socks, unwashed feet.

And here we get memory. It’s not a specific memory, and it doesn’t go on for very long. A lesser writer would be tempted to shoehorn in a whole scene of memory here, but Munro does just enough to convince us that this character has a past, and a real life. And yet it’s not a life we’re invited to view in full detail. This narrator is simply not going to open up to us, or to anyone. But moves like this keep her from feeling two-dimensional, fake, invented for the purposes of the story.

I climbed up on the bench but still could not see out. On the shelf where caps and scarves were thrown, I found a bag with some figs and dates in it. Somebody must have stolen them and stashed them here to take home. All of a sudden, I was hungry. Nothing to eat since morning, except for a dry cheese sandwich on the Ontario Northland. I considered the ethics of stealing from a thief. But the figs would catch in my teeth and betray me.

I got myself down just in time. Somebody was entering the cloakroom.

Here we get projection into the future—what she wants to do, and what will happen if she does it.

You could read the whole rest of the story this way, with an eye just for what goes on in the narrator’s mind. And I hope you will.

That’s all on interiority for now, but if you’re a paid subscriber, please ask me your interiority questions in the comments and I’ll do my best to answer them—and maybe I’ll find one that needs a longer answer and merits a future post.

Rebecca, this is a nice piece. I’m a fan of the levels you're addressing. One thing you haven’t addressed—at least in the cake series—is sequencing: the choice in what detail/phrase/sentence/level goes first. The goal being, of course, how the information is placed in the reader’s brain to create a specific effect. —T

WOW. What a fascinating deep-dive this was. Thank you! I've learned so much. I didn't realize people could smell the raw meat I've been carrying around in oiled paper.