Blurb No More

I'm taking a long blurbing break...but here's how blurbs work, and how to ask for one

I need to exit the world of blurbing, at least for a while. (For those fortunate enough not to know, blurbing is the laborious but necessary process wherein writers must go begging each other for nice words for the back of their book, and should then, in return, read and provide blurbs for many other new books. “Blurb” can sometimes refer to the publisher’s description of the book, but that’s not what I’m talking about here.)

Early in my career I decided that it was my duty to write at least twice as many blurbs as I received. I believe I’ve written about twenty times as many, and I’ve been happy to do it, but I’m making myself take at least two years off from blurbing anything at all.

This post is both my announcement of that fact (as in, if you’re a writer, I probably adore you, but please do not ask me for a blurb) and, as a parting gift to the world of blurbage, a best practices guide for those seeking blurbs. And it might also be a window into this weird part of the publishing world for those who don’t know about it.

Three things broke me:

First, I decided that this year I was going to protect my time and blurb next to nothing, making only the very rare exception for a great reason (a former student, a close friend, etc.) and yet I ended up with about twenty things to blurb this summer and fall alone. So it’s going to have to be a hard-line no blurbs policy for a while. If I make one exception, I’ll make two dozen exceptions.

Second, I got a blurb request for a friend through their publisher. This is someone I like and admire, someone who did something nice for me in the past, and I was willing to make one of those exceptions and prioritize it at an extremely busy time. Blurbing this book meant not working on my own, not doing other things I needed or wanted to do, for the twelve hours or so, spread over several days, that it took to read. When the book came out (and I need to emphasize here that this was the fault of the publisher, not the author), my blurb was not on the book. Not even inside the book. They had over-asked, and my blurb was relegated to Amazon. I’m not writhing with anger or anything, but it really made me question how I was allocating my time.

Finally: I realized that in the past year, I’ve been able to finish only two books in my project of reading my way around the world in 84 books. Two. I had meant to do at least one a month. My current book, The Conscript, is a slim Eritrean novella that I should have finished in two days, and instead I’ve been stalled for months on page 28 because every time I try to go back to it, I remember there’s something else I urgently have to read instead.

What are blurbs and how do they work?

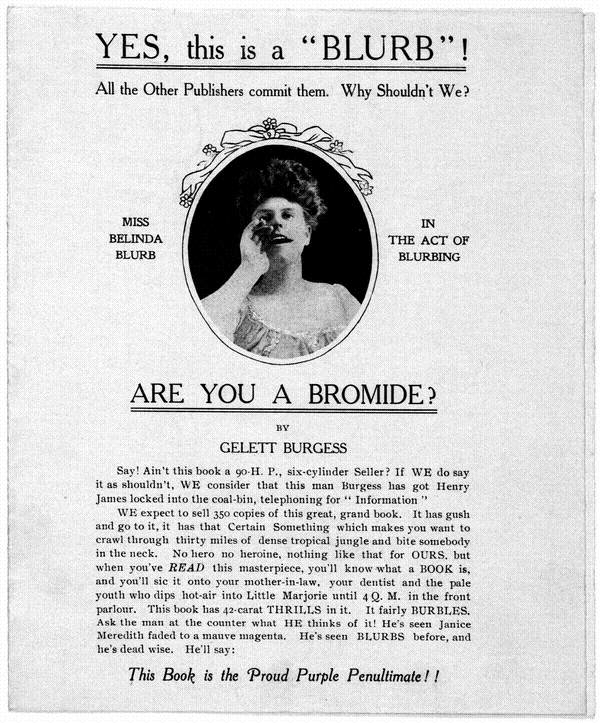

Plenty has been written about the history of the blurb, so I won’t repeat it all here except to say that yes, it’s apparently true that the word originated in 1907 with this fictional character, Belinda Blurb, on the cover of Gelett Burgess’s Are You a Bromide? and I guess we’re all still in on the joke—or maybe we are the joke, hard to tell.

You can read about that elsewhere (I mean, I pretty much just told you the story), but here are seven quick thoughts/pieces of info on the modern day world of blurbing:

Earlier in my career I would never have believed how many blurb requests some authors get. As of this fall, I was getting about five to ten requests a week. And I’m sure there are people out there getting a lot more. I do think it’s important for writers to understand this when they set out to procure blurbs.

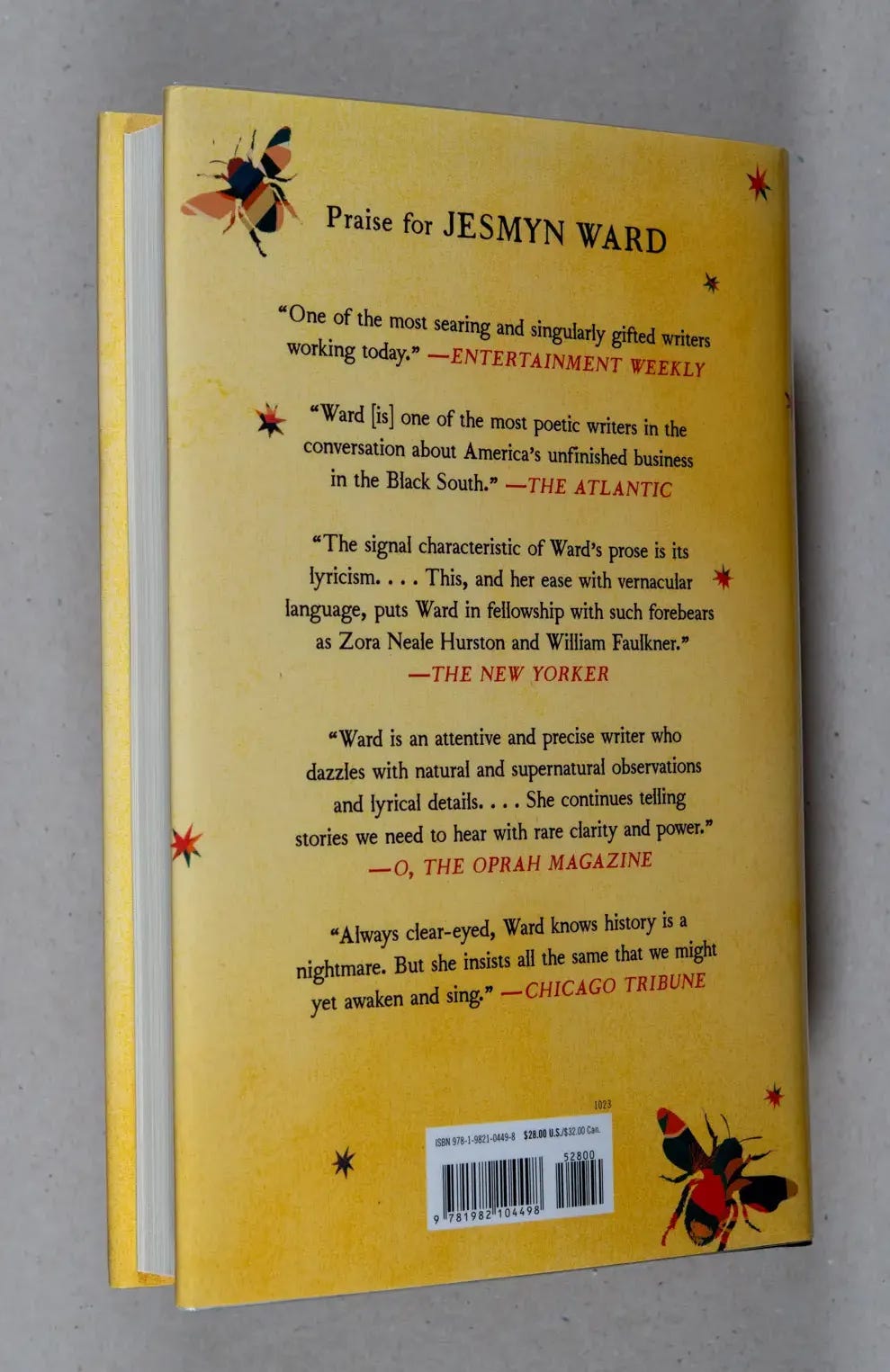

They do matter, and not just to readers. The reviewers who get early copies are going to notice the blurbs, as will the people booking guests on radio shows, booksellers deciding how many to order, etc. I’ve judged book prizes for which each judge was responsible for reading 150 books, and yes, compelling blurbs will probably push something to the top of the stack.

As an author, I pay attention to blurbs for only two reasons:

1) To see what kind of book this is. A book blurbed by Salman Rushdie and Zadie Smith is going to be very different from a book blurbed by Stephen King and Louise Penny, which will be different from one blurbed by Jodi Picoult and Jacquelyn Mitchard.

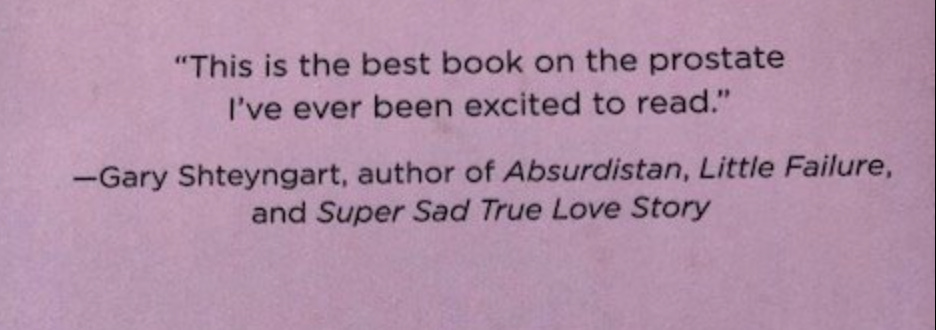

2) To see if there’s any truly over-the-top praise from someone trusted, like “This is the most exciting new voice I’ve read in decades.”

Otherwise, blurbs really only tell you who this author knows or studied with, or who their agent and editor know. Sometimes I’ll look at the blurbs on a debut and go, “Ahh, this person clearly got their MFA at Columbia, because everyone blurbing is on faculty there.” Which still tells me nothing about the quality of the book.Blurbing is hard, and it takes a lot of time. In addition to the reading time (and some of us, including me, are slow readers) it’s hard to actually write the dang things. It’s difficult not to sound trite, and not to repeat yourself from the last ten you wrote.

Blurbs are happening sooner in the process. In the fourteen (!) years since my first book came out, it’s increasingly the practice to procure most of the blurbs for the ARC (advance reading copy), which does make sense (see #2, above)… but it’s also becoming more common for writers and agents to ask for blurbs before the book goes out on submission, as a way of promising potential editors that this book has some good support behind it. And it’s also becoming more common for authors to reach out before they’ve even found an agent, asking a friend or former professor to pre-pre-pre-blurb the thing. All of this is fine, and probably smart, but I’ve never loved the idea of signing off on something that’s going to change drastically before it appears in the world. What if I said it was hilarious and then it gets edited into a serious novel about pancreatic cancer? Now I look like a maniac.

Very few people get to outgrow blurbs these days, it seems. Once upon a time, blurbs were for first novels, or at least early novels. Authors who had already achieved pretty decent success could fill the back cover with “praise for [the author’s last book]” or even (terrifyingly) a giant photo of their face. It seems now like only a handful of mega-bestselling or Pulitzer-winning authors can get away with no blurbs. There are people-you-read-in-high-school out there blurb hunting.

The big, dirty secret: Authors haven’t always read all of (or even any of) a book they’ve blurbed. Sometimes it’s just that the blurber has gotten through 5/6 of the book, the blurb is due, and rather than jilt the writer, they go ahead and write something. (I have done this, I will admit.) But there are plenty of stories of people barely glancing at the book and writing one, or asking the book’s author to write the blurb, which they’ll then put their name to. There’s great risk to that; what if the last twenty pages of the book goes all in for fluoride conspiracy theories, or says something sexist, or just… sucks? Now your name is on that thing forever.

Okay, some practical stuff.

Here’s what a less-effective blurb request looks like:

Dear ____,

When I was thinking of people to blurb my book, I immediately thought of you. My debut novel, LOVE IN THE TIME OF ACID REFLUX, is coming out next year. I would love to send it to you.

Thanks in advance!

And here’s why it might not be effective:

I do not believe you’ve read any of my books, and I don’t have any idea why I’m the person you thought of. Maybe you’ve just heard my name?

You have told me nothing of what your book is about. You’re asking me to spend days reading a 300+ page book; you need to hook me on the premise and plot just like you’d hook any prospective reader.

You have not mentioned a publisher. I’m going to assume, therefore, that you don’t have one and you’re self-publishing. That’s fine if true, but if you’re coming out with Knopf you probably want to say so.

You have not provided any kind of timeline for when I would have to turn this blurb in.

Here’s a much better letter:

Dear ______,

I doubt you remember me, but I introduced myself to you after your panel on “Writing Home” at AWP last year. I loved what you had to say about setting, and after the conference I read and absolutely devoured [the author’s latest novel]—and it became a sort of touchstone for me as I completed edits on my own first book.

I know you’re inundated with blurb requests, but I can’t help taking a shot. HEAVENS TO BETSY is a literary novel with elements of horror, and I hope it might be up your alley. 94-year-old Betsy Sinclair is the last living resident of her nursing home after an apocalyptic solar flash leaves ninety-nine percent of Philadelphia destroyed. Alone with their bodies and her memories, she has all the time in the world to read through the diaries her fellow residents kept—and to learn that one of them knew a lot about the murder of Betsy’s husband in the 1970s.

The book will be published by Snickers Books, an imprint of Harcourt & Schuster, in September of next year. I am, naturally, terrified. If you happened to be up for blurbing, they’re telling me that the deadline for the ARC would be January 3rd and the deadline for the finished book would be June 11th. Would you let me know if you might be interested in receiving a copy, and—if so—where we could send one?

With great appreciation,

Nervous Author

Best Practices for Those Seeking Blurbs:

Give people as much lead time as possible. Ideally six months. Definitely not three weeks.

If you don’t know the author you’re asking very well, explain why you’re asking them in particular.

Sell the person on your book. Unless you’re my friend or student, why on earth would I say yes to a request when all I know about the book is the title? I have infinite other things to read, things that look and sound compelling.

Explain, in your email, when the book will be published, and by whom.

Don’t over-ask. Communicate with your press about how many people they’re asking, as well. Three to six blurbs is plenty. Maybe you could get as many as eight people saying yes, assuming a couple will fall through. Don’t get twenty yeses. You’re taking those authors’ time away from other projects, and other blurbs.

It’s okay (and often helpful) to get back in touch to remind people of the blurb deadline a week or two in advance. Something like “Hi, I just wanted to remind you that the deadline is approaching on 2/12 for my blurbs. Do you still think you’ll have a chance to get to it? I’m so grateful for your time!”

Do not take it personally when an author can’t blurb, or when they don’t manage to answer your email. If you’re asking someone successful enough, their inbox is overflowing with blurb requests.

Don’t take it too personally when someone promises to blurb and then doesn’t come through. It probably was not because they read your book and didn’t like it. It was more likely because they got ridiculously busy and overwhelmed.

Thank the author. Effusively. Some people send little thank-you gifts. At the very least, make sure the author receives a finished hardcover when the time comes. Post the blurbs on social media; this thanks the author and helps your book.

You should not feel embarrassed or awkward to be asking for blurbs. Everyone successful enough for you to approach has, necessarily, been through this from your side of things. When I was about twelve I was mortified to go into Kmart (uncool!) with my mother and asked to stay in the car, where I could hide. She was like, “You do understand that anyone who sees you in the Kmart is, themselves, in the Kmart, right…?” Same principle.

Under no circumstances can you take a professor’s written comments on a story you workshopped, or something someone sent you casually in an email, and use it as a blurb. This has happened to friends. Don’t do it.

Do not claim you got a glowing blurb from an author who recently died. Some guy did this a while back (I’ve been searching for the story with no luck, but please post below if you know the one I’m talking about!) and people didn’t catch on till he’d done it with like three books in a row. I almost admire the nerve of the guy, but wow.

Best Practices for Editors/Publicists:

Cold-sending an advance copy of a book to an author with a note that says “I hope you might have time to read this and let us know what you think!” could not be more cryptic. Are you asking for blurbs? A review? Are you just hoping for a friendly email from me, for some reason?

Good lord, an author who has blurbed a book should not have to beg for a copy of the hardcover. And they’re unlikely to go to the bookstore to shell out $26 for a book they’ve already read. This is someone who already loves the book, whose words are on it, and they are quite likely to post the thing on Instagram once it’s in their hands. You know what I’m not going to post to Instagram? The stack of white paper you had bound at Kinkos to send me originally.

You can squeeze one more blurb onto that cover, or onto the flaps, or in the front matter, if you’ve over-asked. If I can fit all my kids’ summer camp stuff into one car, you can definitely do this.

It’s so, so lovely when you step in and blurb hunt on behalf of debut authors who don’t really know anyone yet. My editor and agent each got me one blurb for my debut (from people they knew but I didn’t), plus my agent magically found the home address of another author who had previously liked my work and had the book messengered to him. I got the fourth blurb myself! And it was terrifying.

Best Practices for Blurbers:

I always go long on purpose, and then tell the author/editor that they’re free to edit as necessary.

Try to get the name of the book into the blurb, so it can work as a standalone quote.

Try to get a couple of useful adjectives in there, so the publisher can pull out just that adjective for the cover, if they want. Like, “Splendid!” - Toni Morrison.

If it turns out that for logistical reasons you can’t fulfill your promise (vague or solid) to blurb, let the author know as soon as possible, and assure them it wasn’t because of the book.

If you have to turn down someone you know or wish good things for, you could always offer that you’d love a finished copy down the road, for sharing on your social media or for general word-of-mouth. Don’t promise anything you can’t deliver, of course. (And askers, if you hear “I’d love an early copy for whatever,” it’s not great form to follow up months later asking why they haven’t posted about it. Word of mouth might mean they’ll read it a year later and tell everyone they love it, or it might mean they gift it. Just take the nice gesture.)

If you’re blurbing and you find a factual error or the kind of slip-up that might not have been fixed in later copy edits, do not tell the author. Get in touch with the author’s agent or editor and let them know. If there’s nothing to be done, they don’t have to tell the already-panicking author. If it’s fixable, they’ll get it fixed.

Don’t promise something that’s not in the book. If the book is mildly funny and you say it’s a laugh-riot, you’re setting readers up for disappointment—and it’s not the author’s fault.

On rare occasions, when I already knew the author’s work but absolutely wouldn’t have time to read the book, I let them know this and volunteered to write a blurb that was more about them as a writer than about the book. This is risky unless you fully trust the author, but it can also help a writer in a pinch. Something like “_______ is a writer of uncommon intelligence and humor” works nicely. (Readers: If you’re on the lookout, you’ll spot blurbs like these. Ones that say nice things about the author and their writing, but not about this book.)

If you’ve already gone to the trouble of blurbing the book, it really is great to post about it online when it’s published and support that author in other ways, too. You might be one of the few people in a position to do that.

One More Parting Gift to You:

For any authors struggling to write a blurb right now, you are welcome to steal any of the following.

For a book you liked:

This book wrenched my guts and broke my heart. A stunning meditation on [cheese] and what it means to [be a mouse] in turbulent times, it’s an assured and ambitious debut.

For a book you did not love and want to say only neutral things about:

This book, set against the vivid landscape of [eastern Nebraska], asks what it means to be human, and what it means to be free. Never before has the story of [the invention of pretzels] been told, but here it is in your hands.

For a book you didn’t read:

Any new book by [Stormi L’Amour] is a major occasion. What a masterful writer!

For a book you actively hated but for some reason are still blurbing:

The most disturbing story about [flour milling] in recent memory. Brave!

For an author you want to keep up all night wondering what the hell you meant:

This is hands down [Blankenship]’s best work!