The Brilliant Lebanese Novel It Took Me Six Months (?!) to Finish

Plus, unhappy updates on Khaled Khalifa and Adania Shibli

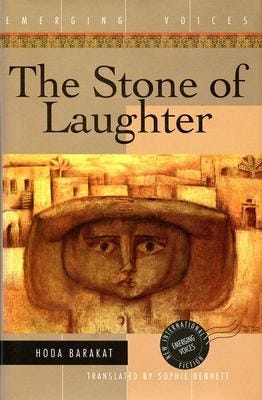

You know how sometimes you have one book that just keeps getting put on hold, and then you realize you’ve been reading it for half your life? In this case, Hoda Barakat’s The Stone of Laughter, the tenth book in my project of reading around the world in translation, took me six frickin months and (appropriately?) traveled with me around four continents, mostly just hanging out in my backpack.

First, an explanation of why I averaged less than two pages a day:

An extenuating factor here is that I was judging Canada’s Giller Prize, which meant I spent May through early September reading nothing but contemporary Canadian fiction. (The final deliberation and prize ceremony are on Monday night, and I’m pretty dang excited. The five finalists are brilliant.)

Then there’s the fact that this fall, I’ve been traveling a lot (Poland, Hungary, Australia, Bali, plus around the US) for book events, and when I travel I go into survival mode and mostly want zippy audiobooks or Love is Blind. (Related: I wish Uche a life of single misery and self-reflection.)

And there’s the fact that this is just a dense book, without a lot of plot-based propulsion. And it’s emotionally heavy. And it’s poetic enough that you want to slow down and read one page three times to make sure you got it all.

But! You need to read it!

You really do. (If you can handle a book about war right now, which understandably might not be the case. But for some of you, this might be the exact book you need at the moment.) And most of you will zip through it much faster than me.

Both written and set during the Lebanese civil war (it was first published in 1990), the book follows Khalil, a young gay (or mostly gay) man left floundering in the ruins of Beirut. The plot, as such: He’s in love with his friend Naji, who leaves the area with his family, putting Khalil in charge of their empty apartment. Naji is killed, and the 1982 Israeli siege of Beirut begins. Khalil wanders the empty rooms a lot, stewing, and sometimes takes refuge with journalist friends (newspaper offices being off-limits in the bombings). Khalil’s cousins move into Naji’s apartment and he falls in love with his cousin Youssef, who is subsequently killed in street fighting. Khalil develops an ulcer which almost kills him, and falls in with a shady older gay man who traffics drugs and arms. In the end (and it’s a hell of an ending) sweet Khalil is transformed into something monstrous, a creature of war and of a broken city.

The genius and poetry of the book are in its essayistic passages. For instance:

Time is not a steed that eats to keep going.

Time is a sugared doughnut. Little pieces strewn about empty, even, of their soft fragility.

In a city like ours, your life is like a butcher’s block. And your time, you stand at the sink rolling your sleeves up over your arms and begin to mince it up into little pieces and eat. Tiny bits which get more minute whenever they are gathered together… the more you mince them, the tinier the bits become, until they vanish. Nothing holds your time together and gives it its essence or content except the bombing. The bombing rearranges the city’s schedule like the calendar of the fast does in Ramadan. Before the bombing—during the bombing—during the long bombing after the bombing—before the bombing. All sorts of bombing.

Everything is minced into tiny pieces, a puff of dust, except during the bombing. On the radio you hear nothing but fragments of words and songs…

Most notably, there’s a lengthy passage about the role of laughter in a city at war. If I reproduced only part of it here, it might sound glib, which is certainly not the overall (or intended) effect—so I’ll just say that the section, which starts with “This is a place where people laugh more than anywhere else in the world,” is alone worth the price of the book and the time (yes, even six months!) of reading. It’s a passage I’ll likely teach.

About Hoda Barakat

According to sources on the internet that I can’t really fact-check, this was the first Arabic novel with a gay main character. Huge if true! (Probably true!)

Barakat, born in Lebanon in 1952, has lived in Paris since 1989, was originally educated in French—and, according to a 2019 interview in Le Monde, needed to study significantly to teach herself to write in Arabic.

From that same interview:

“As long as I write in Arabic about the Arab world, I do not really feel far away. For me, France is an area of freedom in relation to social constraint. I can see things from a distance, be critical. It’s like a country house. It’s not my real home, but I need it."

The English translation, by Sophie Bennett, was published by Interlink World Fiction. I’ll admit here that it was occasionally the density of the translation that slowed me down, and there were some funky things going on with verb tenses—e.g., “In his room he saw her hands. She has slender fingers…”

Which leads me to…

The joy of meeting a book on its own terms

One of the things I love about reading in translation (or reading something historical) is that I don’t stand in any position at all to judge. I can assume that when there’s something I don’t understand, something that doesn’t work for me, it’s not because the author or the translator has failed, but because I’m just not getting it.

I assume that the verb tenses are a faithful replication of constructions that work well in Arabic but less well in English. Ditto for run-on sentences and odd punctuation and a wavering between first and third person that could at times be confusing.

It’s like eating something I’ve never had before and knowing that if I don’t like it, that’s on me and my unrefined palate—rather than, say, comparing this grilled cheese to all the other grilled cheese I’ve had, and my platonic ideal of grilled cheese, and finding it wanting.

Unhappy updates about two of the other authors I discovered through this reading trip:

First: Khaled Khalifa, the author of the Syrian novel I recently posted about, passed away from cardiac arrest at age 59 at his home in Damascus. FSG published his 2019 novel, No One Prayed Over Their Graves, this July; they were kind enough to send me an early copy after I posted about No Knives in the Kitchens of this City, and it looks wonderful.

Second: On October 13th, the organization Litprom “postponed” an award ceremony for the Palestinian author Adania Shibli at the Frankfurt Book Fair—in their words, “due to the war started by Hamas, under which millions of people in Israel and Palestine are suffering.” According to the Guardian, “In its original announcement, LitProm said it had taken the step to postpone the award as a “joint decision” with the author. But Shibli’s literary agency told the Guardian the decision was not made with her consent, and that if the ceremony had been held she would have taken the opportunity to reflect on the role of literature in these cruel and painful times.”

In response, more than 350 authors, editors, and translators from around the world signed a letter of protest, one I resolutely agree with.

The award was for her novella Minor Detail, which I wrote about here. I strongly encourage everyone to read it. And yes, read thoughtful Israeli authors like Etgar Keret too, and read about the history of the region. Read books you agree with and ones you disagree with. Read the words of Hiba Abu Nada, the Palestinian writer killed in an airstrike on 10/20. Read poetry. (I dare you.) Your soul has room for all of it.

The next two books!

I love it when people read along with me (even if you’ve forgotten the book by the time I post about it because you finished it six months ago)…

So here we go, the next two books—and the last two in Arabic, at least for now. (The Yemini novel below, along with The Stone of Laughter, the Khalifa and the Shibli, were recommended to me by the lovely Lebanese-American novelist Rabih Alameddine).

From Yemen: The Hostage, by Zayd Mutee’ Dammaj. This one is very short, and I’m already halfway in. Despite the title, this is—believe it or not—a breezy and sometimes funny book about a young boy raised in the Imam’s palace in the 1940s.

From Egypt: The Open Door, by Latifa Al-Zayyat.

Join me! Also please make me feel better by telling me the longest it’s ever taken you to finish a novel…

I have been reading Bleak House for most of my natural life.

I have been reading Clementine: The Life of Mrs. Winston Churchill for, uh, three plus years? But I haven't picked it up in months now, so I may need to start over. I like it! It is interesting! I just started it pre-pandemic and then I couldn't read anything of substance for a long time and keep reaching for fiction instead.